Before the advent of iced coffee, air conditioning and outdoor din- ing, summertime in New York City was pretty unpleasant. During heat waves the aroma of rotting trash filled the air, horses often dropped dead in the street and heatstroke was a common affliction. It’s easy to see why the city’s well-heeled decamped to the countryside during summer’s swelter. For most of the 18th and 19th centuries, Gotham’s upper crust spent the season at resorts in cooler climes like Southampton and Newport.

The advent of the automobile changed this custom. Cars made it possible for “professional men” to escape the city’s heat for a weekend or even an evening without having to relocate for the entire season. As more and more wealthy New Yorkers opted to stay in town for the summer, the city’s restaurants responded with seasonal fare and dining options that could compete with even the toniest resort towns.

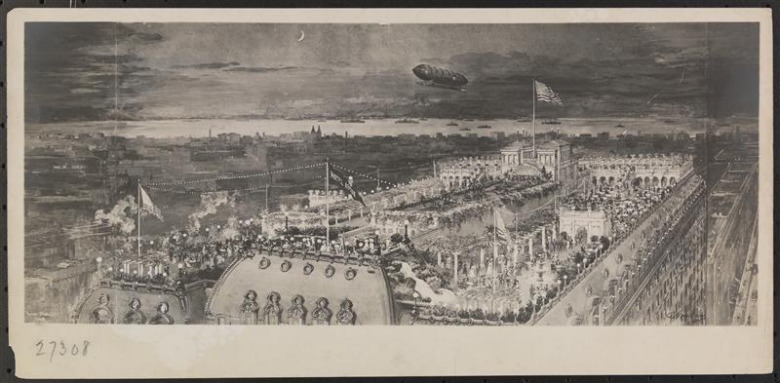

Pre-AC, summer heat made indoor dining all but unbearable, but by the turn of the century al fresco options abounded. The United States Hotel opened the city’s first rooftop restaurant in the 1890s—an innovation that proved immensely popular. Hotels like the Astor, the Waldorf and the St. Regis quickly followed suit and soon Gotham’s roof gardens were the places to see and be seen. Old money elites, nouveau riche, celebrities and artists all rubbed shoulders in the open-air breezes.

The city’s finest rooftop restaurants spared no expense in creating oases of cool and calm. Towering fountains, artificial grottos and waterfalls offered respite from the steamy streets below. In 1910, Madison Square’s grandest hotel, the Hoffman House, unveiled an elaborate system that pumped “iced air” from the basement to the roof garden, allowing patrons to keep cool even during midday lunches. Lavish decoration also added to the transporting effect— the Astor Hotel spent tens of thousands of dollars on lush rooftop landscaping of ferns and even palm trees. In 1905, the roof garden at the Waldorf-Astoria incurred a staggering florists’ bill of $50,000 (a sum of over 1 million in today’s dollars).

Most rooftop restaurants served a light fare. Cold soups, yes, but also gelatines, jellied meats (jellied tongue was particularly popular) and aspics were common offerings, while lemonade, mint juleps and Champagne dominated drink menus. The finest roof gardens catered to an upper-class clientele— some, like the Waldorf-Astoria, were even restricted to members who had been vetted by management. Elitist patrons took pleasure in the vantage point offered by rooftop restaurants—they could literally look down upon the masses in the streets 30 stories below.