All produce that makes it from the market or grocery store to your table has one thing in common: It’s already dead.

Of course death leads to decay, and decay — in addition to perfectly edible food — often gets thrown away. According to Dana Gunders of the Natural Resources Defense Council, “40 percent of food in the United States today goes uneaten.” This waste occurs all along the supply chain, with one of the greatest losses in North America being fruits and vegetables purchased by consumers: 28 percent of these products go to waste according to a 2011 Food and Agriculture Organization study.

Food waste frustrations were some of the seeds of Radicle Farm Company. Christopher Washington, James Livengood and Tony Gibbons came together with a shared disgust and put their skills together to form a small hydroponic greenhouse that is quickly outgrowing its walls. Their innovation is a simple one: They sell their greens alive, still growing in trays so that there is no decay between the farm and the plate. Just snip, wash and eat.

Christopher Washington and James Livengood bring the agricultural expertise to the table while Tony Gibbons brought a finance degree and years of experience working as maître d’ at Gramercy Tavern.

The boys started with a 8,000-square-foot hydroponic greenhouse in Newark, New Jersey, in January of 2014, with the intention of selling to some of New York’s best chefs. Restaurants like Northern Tiger, Amali, Locanda Verde and Gramercy Tavern jumped on board quick due to the superior taste of living food. Gibbons said that the chefs really became collaborators, having a great effect on what they grow.

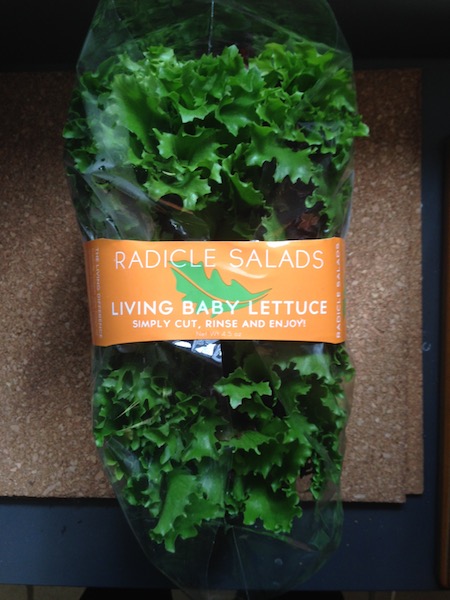

Now, just over one year later, Radicle Greens is moving into grocery stores, too, starting in a handful of Whole Food Markets in New Jersey, as well and through Fresh Direct. The 4.5-ounce packages of baby lettuce, which consist of a plastic tray with soil and the greens sprouting up, surrounded by a thin plastic bag, sell for $3.99. According to Gibbons, when it comes to hydroponics, scalability doesn’t help with cost as much as with traditional agriculture, which is how Radicle Farm can keep prices competitive.

The greens themselves bear little resemblance to the bagged or boxed versions on most grocery shelves. The stems have great crunch and a nutty flavor while the leaves maintain a sheen due to the increased and constant hydration.

I tasted the greens at several stages over five days. The baby greens like the tatsoi and spinach (a mix that the boys call “Shanghai Spinach”) were all snappy and still glistening. The bitter greens like red Russian mizuna were spicier than I have tasted before, but also more delicate. At Radicle Farm’s spot in environmentally conscious co-working space Impact Hub in TriBeCa, we munched a bowl of freshly snipped greens like potato chips.

Gibbons explained that the common “clam shell” packaging, the clear plastic box in which most grocery store greens are sold, does a great job of keeping greens fresh until they are opened. After that all bets are off. Radicle Greens can be, but need not be, refrigerated.

My tray of greens in its original packaging (pictured at three days) has been sitting out on my kitchen counter for five days now and looks very nearly as good as the day I got it. As far as I can tell, nothing’s changed.

A few things are still being worked out to get the greens ready for wide grocery release. The Radicle package doesn’t fit most stores’ existing produce displays and the founders are still concerned that customers will not fully grasp the difference. But so far, the stores that do sell Radicle Greens can’t keep them in stock.

When we spoke to Gibbons in late March 2015, the new 50,000-square-foot greenhouse in Utica, New York, that will allow this expansion was just starting production. When asked why no one else is doing this, Gibbons said with a smile, “We get that question a lot.”