On a Thursday evening in January, an older woman with a stack of silver bangles climbing her wrist steps up to the bar at Peter McManus Café on Seventh Avenue at 19th Street. She and her friend debate about what to order—she doesn’t drink beer—and settle on wine, a red. “Which?” the bartender asks quickly. “We have a malbec, cabernet and pinot noir.” While I silently root for her to try the malbec, they both go for the cab. Still, who would’ve expected options at a place where there are payphones, where the game is on the TV, where an Irish and American flag fly by the door, side by side?

McManus Café has been in this spot since 1936 (the original, at 43rd and 11th, opened in 1911 and closed during Prohibition) and under the management of 36-year-old Justin McManus since 2007. When he took over from his father, who took over from his father and so on, there were rumblings among the regulars that the Cornell graduate would change too much.

“There was a little piece of wood, right near the phone booth,” he tells me, gesturing toward the center of the bar. “Just a wooden plank that was 10 inches, maybe a foot out that held a phone book. This piece of wood was always the biggest bottleneck when we were busy.” So he had it removed. “Even my dad was pissed at me,” he says. “I heard it for months. This was 10 years ago and people still bring it up.”

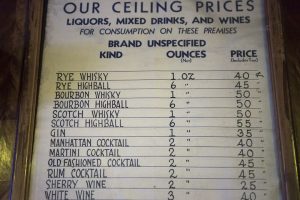

McManus has had to make more significant changes, too, but no one’s complained about the new tap lines, credit card readers or flat-screen TVs. What he does have to keep an eye on, though, are the selections behind the bar. Whether it was the wave of younger folks a decade ago asking for PBR (they’ve never carried it) or how he initially resisted Red Bull’s ascendance, as the head of an institution he’s had to consider where to change and where to stay the same in a city that will never cease to move along without you.

Those who complain about the removal of a phone book holder might have history on their side. According to Steven H. Jaffe, PhD, a curator at the Museum of the City of New York, the Irish bar has played a key role in the city’s recreational life since the mid-19th century, when the Great Famine saw Irish immigrants fleeing to New York.

“The neighborhood ‘saloon’ really became a community center for these folks,” he says. “It was where you could unwind over whiskey or beer after a hard day’s work as a cart driver, longshoreman, factory hand or laundress. But it was also where you could learn the latest news from the old country, find a job and make other social connections that could help you survive. As a result, saloon keepers became important figures in Irish neighborhoods like Five Points, Hell’s Kitchen and across the river in Brooklyn. Running a bar often was the first step in a political career. Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party machine in New York, promoted saloon keepers to important positions and ran them for political office. In fact, by the early 1900s, Tammany was being run by a saloon keeper, ‘Silent Charlie’ Murphy, one of the most powerful politicians in America.”

When Sean Muldoon and Jack McGarry, barmen from Belfast, opened the Dead Rabbit (named for an Irish-American street gang from the 1850s) down on Water Street in 2013, the perception of the old-school Irish bar in the city began to shift. Though their ground-floor pub has a kitschy layer of sawdust underfoot, black-and-white photos tacked to the beams and the patches of police departments over the bar, where they didn’t follow the pattern of a traditional pub was in their cocktails, which focus on whiskeys but branch out into sherries, vodka, agave spirits and more. That focus on considered drinks earned them the top slot on World’s 50 Best Bars in 2016.

“Our narrative is to bring the Irish pub into the 21st century. Like Irish whiskey, the Irish pub has been pigeonholed as an inferior product,” says McGarry. With the exception of places like McSorley’s Ale House, which opened in 1854 and is still operating in pretty much the same way—light or dark beer are your options; the cheese plate is served with saltines—he didn’t see too many pubs like the ones he loved back home. “There’s no music, no TVs, and the emphasis is on the staff,” he says of McSorley’s. “The service is very authentic—brash, quick, with no fuss.”

While they’ve chosen the back-home approach for their foundation, it’s what they’ve changed that’s allowed them to find success. “We’re offering something different. We offer attitude; we’re contemporary; we pay homage to Irish history, but we’re not living in the past, nor are we afraid to evolve,” McGarry says. “Our concept is historic but we’ve adapted it with a young, dynamic team and high-standard cocktails. We take the music very seriously and we reinvest a lot of money in our bar.” They’re planning an expansion into the building next door, and writing a book about Irish bars, whiskey and cocktails.

Where the notion of an Irish bar gets truly turned on its head is at the West Village’s The Spaniard—because, as you can tell by its name, it’s not an Irish bar. Its owners David Mohally, Ruairi Curtin and Mark Gibson are Irish-born, however, and there’s something there in the hospitality, in the lack of pretension, that makes all of their bars feel like they’ve been around a long time, much like any pub with a neon Guinness sign in the window. In addition to the Spaniard, they’ve got the Bonnie, the Penrose, the Wren, Sweet Afton and Wilfie & Nell scattered around Manhattan and Queens. Bua, in the East Village, was their first venture over 13 years ago; its name is Irish for “victory.”

“I quickly realized that the corporate world 9 to 5 wasn’t for me,” says Curtin, who’d been working for the Irish government, “and that’s when I sat down with the two boys and discussed opening a bar.”

Luckily, one of them actually could mix drinks. “I started working in bars like most Irish people do to make money,” says Gibson, who’d followed his now-wife to New York. “I’d always worked in bars, all the way through college in Ireland, and then that became the main thing that I was doing over here.”

“We started out innocently, not knowing a lot about the industry,” says Curtin, who thinks their blind start allowed them to figure out their own way of doing things to create the kind of bars where they wanted to hang out themselves. With six bars opening in the time since they cut their teeth with Bua, one can see that there was something to that lack of strategy. Each bar of theirs has suited its neighborhood, filling the need for a watering hole where you might not have realized you needed one. The Spaniard feels big and classic but cozy all the same, and the food is bar-friendly and approachable while not short on vegetables. Their cocktail program goes for that same vibe and won me over, personally, with the mini Lunchtime Martini, made to your preference.

With the bars they’ve opened, the Bua Group has taken classic Irish hospitality and made it their own, while the Dead Rabbit sought to redefine the Irish pub for the serious cocktail drinker. At McManus, they’re trying to simultaneously keep tradition alive while evolving as much as possible. In considering them all, the definition of the Irish bar becomes elusive; neither history nor drink list nor name can confirm what you’ll find when you take a stool. Perhaps it’s just something to ponder while you’re there, sipping your whiskey (or wine).