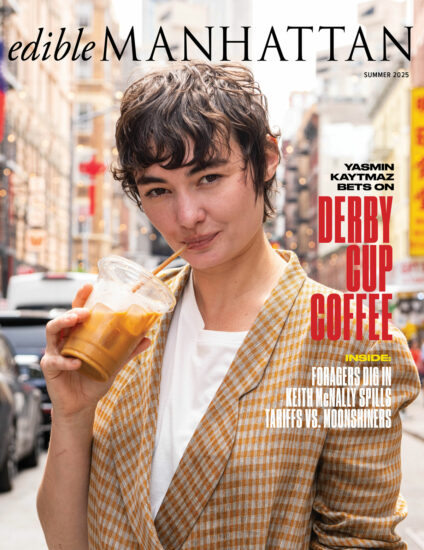

At 11 a.m. on the third floor of a building in Midtown, a commercial kitchen hums. A group of cooks wearing black chef coats methodically chop vegetables next to a stack of wooden pallets loaded with fresh produce.

The scene could be a kitchen gearing up for dinner service or a buzzing incubator, but it’s neither. The folks preparing food are enrolled in the culinary arts program at Fedcap Rehabilitation (or just Fedcap, as it’s called), a nonprofit organization founded in 1935 by and for people with disabilities.

Originally founded in New York City as the Federation of the Crippled and Disabled, today’s Fedcap now also operates in parts of New Jersey and Washington, DC, and serves anyone with a physical or mental limitation that, as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), hinders “major life activities.” This includes people with a history of disability who may not currently be disabled, and the ADA does not specifically name all of the qualifying impairments.

The culinary arts program was founded in 2000 to provide free culinary training, food handling certification and a small stipend to students in a nurturing environment where they can develop professional skills and build confidence without fear of harassment or discrimination. This type of vocational training isn’t unique to Fedcap Rehabilitation, but given the structural barriers for the individuals they serve, the diligence of Fedcap’s work stands out: 486 students have graduated from the program with a 72 percent rate of successful job placement.

“The smells, the sounds, everything about it—I can lose myself here and I don’t have to think about how I’m depressed. I don’t have to think about my anxiety and paranoia, or if I’m doing anything wrong and people are watching me,” says Jonathan Colon, a 28-year-old Bronx native who came to the program in early 2018 on his therapist’s recommendation. Working in the kitchen has been “more therapeutic than anything else I’ve done,” he tells me.

Read more: Food Has Always Been Medicine for this Soho Nonprofit

A Widespread Problem

Workplace discrimination is a problem behind and beyond the swinging doors of the professional kitchen; the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reports that over one-third of employment discrimination charges relate to disability rights and often overlap with other workplace abuses, including racism, sexism, ageism and homophobia.

The rates of disability are similar across black and white populations, between 13 and 14 percent, but there’s a stark racial disparity in rates of joblessness: Black people with disabilities experience an 11.2 percent rate of unemployment compared to 7.3 percent of whites. Hispanics fall in the middle at 9.8 percent and Asians report the lowest at 7.1 percent, according to the 2019 Bureau of Labor Statistics report.

Nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population lives with a disability, and roughly half of this group are over the age of 65. The inadequacy of disability services coupled with discriminatory employment practices increases the likelihood of poverty. The National Council on Disability reports that 12 percent of the working-age population has a disability, out of which 32 percent are employed. They represent more than half of people in long-term poverty and are twice as likely to work part-time hours, often paid with subminimum wages—an allowance given to employers under Section 14(c) of the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Students like Colon are referred to Fedcap Rehabilitation through the New York State Adult Career and Continuing Education Services–Vocational Rehabilitation (ACCES-VR), which in-turn provides funding to the program. Graduates receive job placement assistance, professional development and internships through the Food Arts Center, Fedcap’s social enterprise arm that connects students with food professionals throughout the city.

Cooking helps Colon thrive under day-to-day challenges and has motivated him to dream about eventually opening his own restaurant. In the past, he’s experienced bullying for being bisexual and feels uneasiness in public places, but at this kitchen, the tasks at hand mute the noise outside allowing the worries of his mind to dissipate. When Colon enrolled, he couldn’t hold eye contact with others, but now he works on staff in the kitchen overseeing deliveries, managing the program’s social media and assisting students. “It used to be hard for me to shake someone’s hand and now I help clean people’s cuts and bandage them up,” he grins.

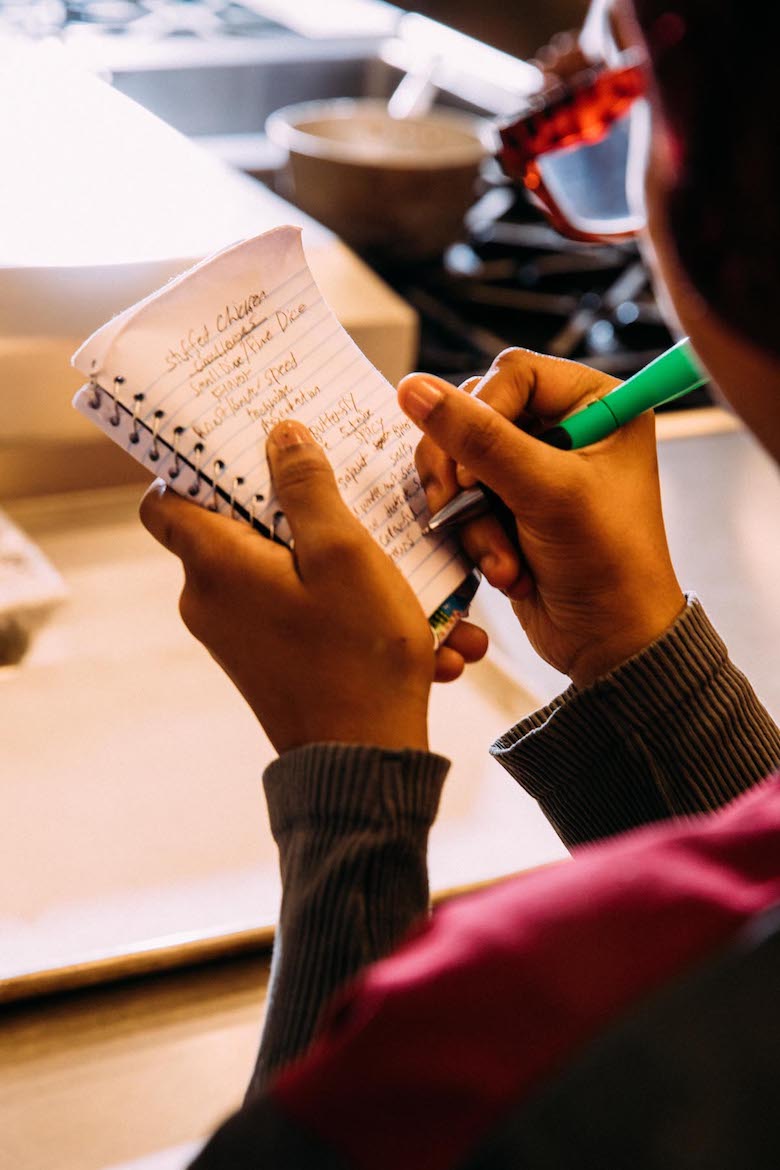

Regardless of age, ability or exposure to cooking, the program tries to meet students where they are and not rush their process. “I have students who are on day one and students who are at day 261, but it’s important to instill in each of them a sense of confidence that they’re capable,” says chef Alexis Aquino, a 37-year-old Queens native and the head culinary instructor at Fedcap Rehabilitation. His goal to make the training applicable and empowering for each student “is a dance,” he admits. “But I’ve discovered that people are amazing and they can’t wait to show you, if you give them the space.”

A Way Forward

Read more: For High Schoolers, an Interdisciplinary Food Curriculum Grows Nationwide

Aquino took the program’s old curriculum, defined by long hours of uninterrupted class time, and transformed it into an interactive student-centric model that alternates short lessons with competitive cooking challenges by which he measures retention and growth and ensures each student’s creativity has a chance to shine.

Aquino’s educational method evolved out of years of teaching culinary arts to high schoolers at Harlem Children’s Zone, a local nonprofit where he worked fresh out of school at the Institute for Culinary Education. “God forbid I had been in a restaurant that whole time,” he sighs, noting how the casual tyranny by which many chefs run their kitchens would have warped his approach to culinary education and marred his ability to earn students’ trust.

“I’ve worked at certain places where if you make a dish and they don’t like it, they plop it onto the floor and tell you to clean it up,” says Dominique Santos. The 23-year-old Harlemite joined the program in the summer of 2018. She’s worked as a barista, server and grocery store manager, but wanted to earn her food handler’s license and learn professional cooking techniques.

“I thought it was a good opportunity to get more skills and be able to take better care of my child,” says Santos, who juggles school and work as a single parent on a limited income. “It helps to know that I can make something myself.” Santos experiments with cooking at home and earns extra money working at Food Arts Center events. She hopes to eventually run her own catering business.

Enrollment is ongoing which allows new students like Santos to work alongside seasoned ones like Billy Ross, a 58-year-old cook who has worked in New York City kitchens for as long as he’s been a matriculating student at Fedcap Rehabilitation—roughly 30 years. He recalls the first dish he prepared after returning last year to complete the culinary arts program. “Fried grits with yellow zucchini and roasted red peppers on top,” he beams.

Employers benefit from hiring people with disabilities, Aquino believes, because they take pride in work that others take for granted. For example, gaining full-time employment with benefits is a recent victory for Valerie Grayson, a 55-year-old from the Bronx who struggled with substance abuse for decades before enrolling at Fedcap. “I got tired of being on the streets, so I went to school and changed my life,” says Grayson. She took on leadership opportunities at the program and gained the experience she needed to secure not only a full-time position but recognition as “the leader that she is,” says Aquino.

Grayson graduated from Fedcap last summer alongside Colon, who gave the commencement speech—a feat emblematic of the challenges they’ve overcome. “I’m happy for myself,” Grayson tells me, then pauses to add, “And we’re happy for each other.”