These days it seems every new restaurant offers cuisine billed as “New American.” You know, farmhouse-gone-gastro: The slow-poached, free-range quail egg astride braised spring greens. Or the roasted Berkshire chop paired with creamy grits, wilted wild mushrooms and a few house-pickled ramps.

Which is why we were surprised by the title of Marcus Samuelsson’s new book. Star of Midtown’s Michelin-starred Scandinavian spot Aquavit, we still think of him as more of a seared Arctic char with cauliflower puree and a smoked egg yolk and lingonberry compote kind of guy, paired with those infused vodkas we can’t get enough of. But his latest book, New American Table, is no hushed homage to our country’s current take on haute cuisine. Rather, it’s an intense and vibrantly colored love letter to our country’s multi-culti culinary diversity, its patchwork pantry inspired by New Americans-that is, immigrants just like Samuelsson.

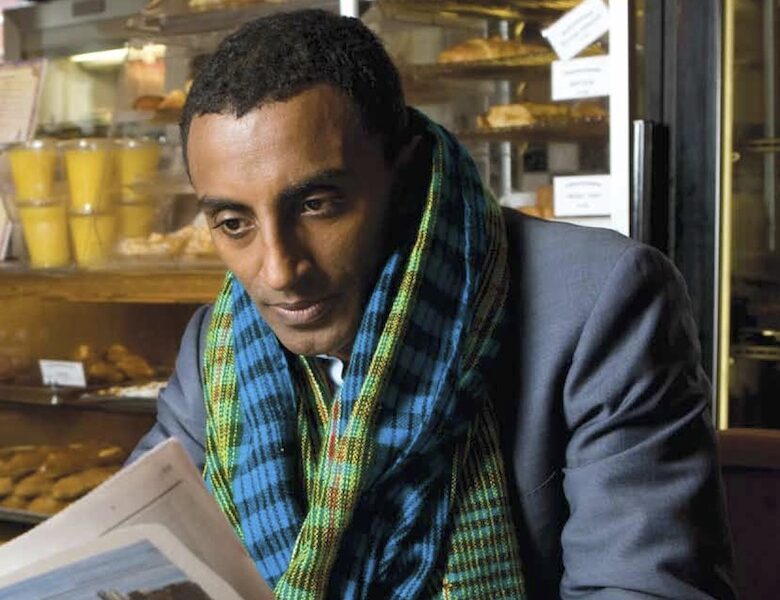

The Ethiopian-born, Sweden-raised New Yorker says the riotous American melting pot surprised, delighted and inspired him when he moved here in 1991. And while the book celebrates our nation’s culinary diversity (California taco trucks, Kansas City steaks, Michigan cherries and Chicago’s Nigerian cooks), at its heart this book extols the flavors- French, Indian, Polish, Senegalese, Chinese or Jamaican-of New York. This city’s palette of palates, says Samuelsson, made him the chef he is today.

“I came here because of the diversity,” says Samuelsson, who left a top restaurant in France for our fair city’s flamboyant flavors. “It was so easy and so matter of fact. I had to come to New York. It just felt right for me. And that’s what this book is about.”

Twenty years back, when he was just an intern at Aquavit, he was amazed at the diversity of tastes on offer in his new hometown. Where else can you get real delicatessen fare, handmade beef patties, five regional styles of Chinese and four-star French-all within a few blocks? “To be connected to Gray Kunz at the St. Regis”-the younger Samuelsson saved for weeks and borrowed a waiter’s suit to dine at Lespinasse, Kunz’s now-departed four-star Asian-fusion restaurant-“and at the same time have Chinatown, the whole spectrum, that sort of blew me away.”

Soon he was spending every spare minute pursuing edible experiences-and hitting markets for ingredients to experiment with in various home kitchens. (“I’ve lived on Seventh Street and in Stuy-Town and Hell’s Kitchen, and I’ve been robbed in every neighborhood,” laughs Samuelsson. “But I have no regrets. It’s the New York experience.”)

Samuelsson forayed deep into Chinatown and Koreatown, eating his way through the west African restaurants in Harlem, where he now lives and will soon open a restaurant-including the Senegalese Les Embassades, which inspired the New American Table’s lamb stew with yam and morning glory.

He also relished the kinds of places found only in New York, some sadly since shuttered. There was the madness of the original Shopshin’s. (“He didn’t give a shit,” marveled Samuelsson of the now legendary Kenny Shopsin. “I mean that in the best way possible”), or Kiev in the East Village, the 24-hour Ukrainian diner where the chicken soup reminded Samuelsson of his grandmother’s and the dumplings inspired his recipe for trout pierogi.

He savored Southern-inspired shops like Jezebel’s in Hell’s Kitchen: “I was fascinated,” says Samuelsson. “There was this drug mecca outside and inside were rock stars and Denzel Washington eating soul food.” And at the grungy M&G Diner in Harlem, Samuelsson always got egg sandwiches and grits-which appear in New American Table smothered with wild mushrooms-and took his future wife on their first date. “It was like a test,” he recalls. “‘I said let’s have breakfast,'” telling his buddies, “if she can hang here, it’s a go.'”

He loved Curry Hill, the Indian enclave in the East 20s, both for its authentic ingredients and for the juxtaposition to its upscale environs: “This is right off Park Avenue. All of a sudden: Yeah!” At Kalustyan’s he discovered exotic Indian staples like the black mustard seeds he’d never cooked with before, but soon made into a standby sauce.

He cites chefs of the period like Kunz, Charlie Palmer, Alfred Portale, Jean-Georges Vongerichten and even Rocco Dispirito as mastering the melding of these kinds of ingredients with formal culinary techniques at the same time if not before he was. “I knew those ingredients,” he says, “but I never knew them with butter or veal stock and that type of French setting.”

He was especially inspired by chefs like Portale and Dispirito who cooked with what they wanted to, rather than what they might have been expected to based on their backgrounds. “So many American guys,” Samuelsson says in appreciation, “were so invested in cuisines other than their own.” He recalls his roommate at the time, who helped open Vongerichten’s Southeast Asian fusion palace Vong. “He would say, ‘Oh we’re doing roasted monkfish with carrot-ginger broth tonight,'” says Samuelsson. “That blew me away.”

Global peasant food gone haute might seem clichéd now that David Chang does Peking duck buns as party apps, 15-year-olds are tweeting about their galangal panna cotta and Samuelsson himself is honored at globe-trotting shindigs like last month’s annual tasting event for the youth-oriented, non-profit Careers through Culinary Arts Program.

In that Before-Chang era, sourcing nearly required sorcery. When Samuelsson phoned a Chinatown shop to order lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves and galangal, the owner laughed off delivering outside the neighborhood. “I had to go down there in person with cash,” Samuelsson says.

And while the chef couldn’t do what he wanted at Aquavit when he first took over in 1994-“I was 24, and I wasn’t a known chef,” he says-by exploring the flavors of the city’s many “New American” cooks he came to understand that what he wanted to do as a chef was help make a point: “Fine dining is not owned by a clique of Europeans.”

Get Marcus Samuelsson’s recipe for trout pierogi. You can also win your own copy of New American Table: Just tell us about your own favorite inspired-by-the-city’s immigrant foods recipe in an email to info AT ediblemanhattan.com. Just be sure to put New American Kitchen Contest in the subject line.

Daily inspiration: The Franco-Senegalese spot Patisserie Des Ambassades is one of Samuelsson’s favorite Harlem haunts. Photo credit: Francine Daveta