One of the underappreciated perks of the Edible Communities annual meeting–when publishers from the four corners of the nation (and Canada) gather–is the indigenous booty folks haul into town from their home community. Displayed on a table near the main meeting room were some half-pound bags of Stumptown coffee (courtesy of us), Rancho Gordo dried beans, Ojai pixies, Piggery foie gras, and a veritable who’s who of America’s small-batch food movement.

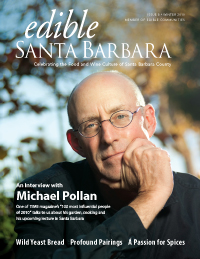

Even better, publishers bring a few stacks of their latest issue, laid out on tables, floors and elsewhere like so much food writing eye candy. I hauled a couple dozen of these back to New York, and they sit in a stack by my desk. Among the most dogeared editions is the Winter 2010 issue of Edible Santa Barbara that includes a cover interview by Edible Santa Barbara editor Krista Harris with Michael Pollan, in which he riffs on how he uses beans in the garden, what his next book is about, and why he’s spending more time in the kitchen.

“I’ve been taking cooking lessons,” Pollan notes, “something my whole family gets involved with—and it’s a whole different experience, and it’s a lot fun. It’s a great way to socialize. I’ve been fantasizing about a new concept of the dinner party where the guests get there long before the food is ready.” The 36-Hour Dinner Party he chronicled in the Times offers perhaps a glimpse of this concept.

But the cooking is also a great example of Pollan’s hunch that the answers to our national food crises will not be found entirely in the realm of policy and science, but in our own daily lives. For instance, of his gardening he notes: “I plant a lot of fava beans, mostly for the soil conditioning, but we eat them as well. . . [Gardening is] very satisfying. I mean, I do it for the pleasure of the work as much as the produce that I get. I enjoy working in the garden. It’s a really nice respite from writing.”

But much of the interview does center on cooking–or lack thereof. “The trends in cooking are not very encouraging,” Pollan explains. “Basically it’s been going down as long as people have been keeping track.” According to Pollan’s research, there are small glimmers of hope: more people buying from the bulk food bins, experimenting with off-cuts of meat, and a bit more eating at home tied to the recession. “But that doesn’t mean that people aren’t having processed food at home. You really have to break it down and see whether people are buying TV dinners and their modern equivalent or actual ingredients to cook with.” Still, he notes that “men are putting in about twice as many minutes in the day as they were 20 years ago,” and families are slowly realizing that cooking is best done as a social activity, not a solitary one.

“The more I work on these issues having to do with our whole food system, the more I realize that our problem is a cooking problem,” Pollan continues. “If we’re not going to go back to the kitchen, it isn’t really clear that we can have this renaissance of local agriculture go very far or that we can tackle this problem of obesity and Type 2 diabetes and all the chronic diseases linked to diet. . . So unless we take back control over that process—that really important process—I think that there’s a real top on where this food movement can go. I want to address that. I want to write a book that doesn’t preach to people about cooking but simply gets them excited about it by watching this education unfold. That’s my hope.”