If the Glockners, the Moores, the Gumpertzes, the Rogarshevskys and the Baldizzis shared one thing in common besides their address—all lived at 97 Orchard Street between the 1860s and the end of World War II—it’s that they cooked. No matter the size of their cramped, filthy, sometimes unlit and often unplumbed tenement kitchens (these days tended by the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, which occupies the building they once called home), these five immigrant families turned out the tastes of their homelands at least three times a day, be that herring salad and veal schnitzel, pea soup and brown bread, gefilte fish and noodle kugel, apple strudel and goulash, or simple spaghetti con agile e olio.

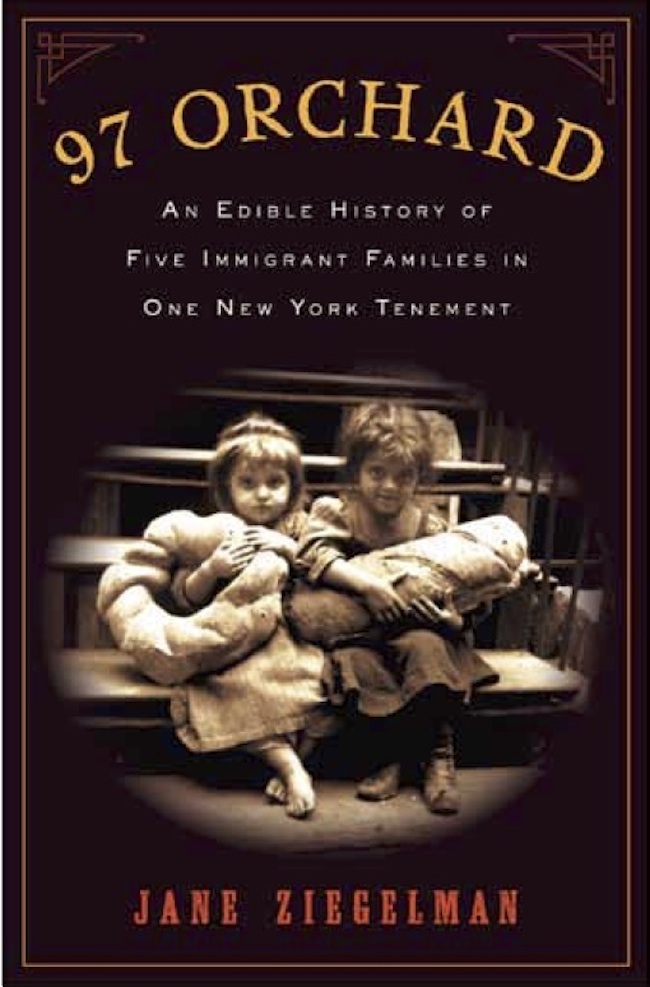

Each of these culinary traditions (German, Irish, German Jewish, Russian-Lithuanian Jewish and Italian, respectively) is a chapter in Jane Ziegelman’s new book, 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement. Ziegelman, a teacher and librarian, will direct the Tenement Museum’s future culinary center, where she’ll bring to life the old-fashioned, extreme DIY foodways so many New Yorkers now hunger for.

Ziegelman researched the book by poring over old Lower East Side newspaper clippings, immigration documents and memoirs, letters, shopping lists, menus, recipe collections like Aunt Babette’s Cook Book, emblazoned with the Star of David, and photo after photo of impoverished families shelling nuts atop a stained tablecloth, laundry hanging overhead and children running underfoot.

(No matter how small your apartment feels, it’s hard for the modern Manhattanite to fathom the cramped quarters of Lower East Side tenements. The stories reenacted by the staff at the Museum put our complaints of slow elevators to shame—consider hauling pails of water, babies, laundry and bloody veal bones up multiple flights of stairs in the dark.)

Ziegelman’s study of these immigrant kitchens considers meat and potato hash and gefilte fish; pickles sold from pushcarts below; German bakeries; Irish lunchrooms; dandelion greens foraged by Italian matriarchs; and the convenience of the Jewish-made knish as a carefully packaged “to-go” food for workers who didn’t have time to come home for lunch—they’d instead hit knish alley, aka Houston Street.

These tastes shaped our city’s culinary landscape, and our country’s, too: foods like bagels, pizza and all manner of pie unified people across cultural identities, and now, stripped of their immigrant status, are considered classic American eats. And while we’ve long since given up on gefilte fish joining that list, we’re still holding out hope for the knish.

Photo courtesy of Harper Publishing