In the wake of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008, Adam Ford and his wife Glynis headed for the hills. Or the Alps, actually. There, in the middle of a therapeutic hike they walked into a café in Courmayer and were offered vermouth at cellar temperature, in a wine glass, as an apéritif. The taste was revelatory to the East Coast lawyer, bearing no resemblance to his preconceptions about the mass-produced vermouth he used to wet his Martini back home, where the world was collapsing.

At a recent talk hosted by the Culinary Historians of New York, Mr. Ford, in black bit loafers, with a snug jacket over a T-shirt bearing a large $ sign, spurned the provided microphone to talk his audience of mature culinary history buffs and a smattering of focused hipsters through the evolution of vermouth. Arguably, he said, it could date back 8,000 years, to the Neolithic period in China. A murmur rose from those assembled on the freezing New York night.

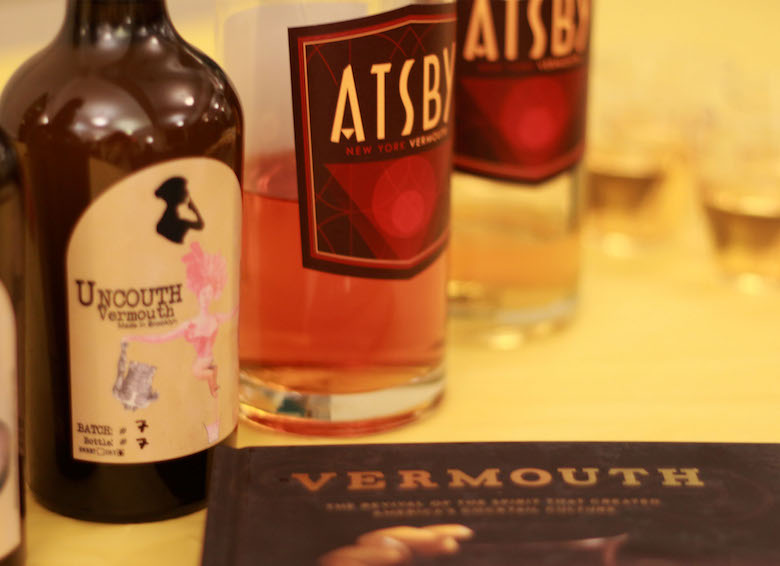

Ford is the author of Vermouth (Countryman, 2015) — a good-looking book rich with archival backstory and confetti’d with appealing cocktails — and the founder and producer of Atsby, the first commercially produced vermouth in the Northeast.

The post-crash Alpine awakening led to a search for facts, which were hard to find, he said, over the hiss of the rejected amplifying system. His growing interest in fortified wine was hampered by a dearth of online information, and oft-repeated vermouth fallacies, so he went burrowing into archives in public libraries to trace the origins of the drink that most Americans viewed as a sidekick to serious spirits.

From ancient China by way of the Mediterranean, Ford’s talk travelled to vermouth’s late 19th century New York boom, when cocktails like the Manhattan were born, using inverse proportions of what the 20th century high-proof cocktail came to be (Atsby is an acronym for the Assembly Theater on Broadway, described by the author as “the liveliest place in New York City [in 1859], attracting a new breed of bartender”).

Also in attendance was Ford’s friend and fellow vermouth producer Bianca Miraglia, in cat’s eye granny glasses and fur poncho, who from time to time offered expletive-riddled and encyclopedically interesting interjections. Her delivery cheerled her own brand, Brooklyn-produced Uncouth Vermouth (its label depicts a lady with her finger up her nose). She describes Ford as an “artist, producer, negotiator,” whose approach is “not about who’s right, but about getting the right answer.”

Atbsy is made with North Fork Chardonnay and is fortified (after “about a month” of cold-steeping with herbs and spices) with Finger Lakes apple brandy; U.S. law, explained Ford, stipulates that vermouth must contain a fruit distillate, whereas E.U. law allows any alcohol to fortify the aromatized wine. But Ford goes on to challenge all definitions of vermouth in an essay in his book that pits Aristotle against Ludwig Wittgenstein. The author-lawyer-vermouth-maker double-majored in philosophy and history.

European vermouth should also contain wormwood (Wermut, in German) to be considered legitimate. Ford’s does not, Miraglia’s does: she uses mugwort, also called common wormwood, the locally invasive Artemisia vulgaris (see my story in the next issue of Edible Manhattan) and, like Ford, relies on a locally-produced wine and spirit base.

During the talk tastings were distributed. Miraglia’s Wildflower contains “20-something flowers” (many domesticated, like carrot, dill and fennel, plus ever-present mugwort — all harvested locally), while her Hops featured that harvest infused just six hours after it was picked on Long Island.

Atsby’s pale yellow and deliciously floral, but dry, Amberthorn contrasted with the label’s darker, sweeter and distinctly bitter (this taster had a cold, which would have skewed her perceptions heavily) Armadillo Cake, which is infused with 32 botanicals, heavy on Asian roots and seedpods, as well as, surprisingly, shiitake mushrooms. Atsby’s botanicals are imported.

Referencing the vermouth Renaissance of the last three years, Ford remarked wryly that when he visited Astor Place Wines in 2010, there were two vermouths on the shelves, at the back. Now, he says, there are 45, up front and center.

And lest modern vermouth acquire the taint of its predecessors, Miraglia stood up and exhorted the audience to “for fuck’s sake keep it in the fridge, otherwise it’s a slow climb to vinegar — with many stages of delicious in between.”