It was a flavor-popping moment in Marcus Garvey Park last summer. Growing at knee height in June, the mugwort I picked for dinner was telling me something new.

It was a flavor-popping moment in Marcus Garvey Park last summer. Growing at knee height in June, the mugwort I picked for dinner was telling me something new.

This city herb was well known to me. My battered Moleskines are bursting with recipes I have developed for Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort’s botanical name), using the leaves, seeds and even the winter stalks (great kebab skewers). Its flavor is sage-rosemary and intense. But, in the connected way of digital things, it took transcontinental voyeurism to reveal the alcoholic potential in the weed.

For years I have been watching a West Coast friend and forager, Pascal Baudar, develop and define native Southern California flavor, interpreting local flora in food and drink. More recently, I have eavesdropped on the experiments of South African wild foods chef Kobus van der Merwe, who champions the indigenous flavors of his Sandveld coastline—and who was tinkering with a local vermouth. I was intrigued by these processes of place.

Infusions and ferments are part of my foraged repertoire, but it was not till that mugwort moment in Harlem that I considered the wild possibilities of an herbally driven, hyperlocal vermouth. The chief ingredient was in my hands. Even though some modern producers eschew it, Artemisia—or wormwood (wermut in German)—is considered the defining component in dry vermouth. Definitions are sexy, and interpretation a turn-on: Mugwort is just another species of wormwood; let the improv begin. I started researching vermouth-making, not appreciating till then how many botanicals (20, by close-lipped accounts) are blended in the dry Noilly Prat, a staple in many cocktails and my own kitchen.

In the Northeast we are surrounded by indigenous aromatics. Few are known to most chefs and mixologists, let alone eaters and drinkers. And among these locals grow fragrant exotics like mugwort, which can dominate and threaten local flora. For the aspiring alchemist, this floral melting pot is heaven. I performed some aromatic math: In two columns I compared time-honored vermouth ingredients with what grows locally, and mentally tasted the possibilities. Then I went foraging.

I made three vermouth versions in 2015: early summer, Harlem; late summer, Brooklyn (we moved); and then an unexpected spring version in Cape Town. The learning curve was steep. And about steeping—knowing how long to infuse each ingredient is vital.

While large-scale commercial vermouth producers use stills to generate their flavored fortification, we must turn to the hard liquor shelf at the local store. Stoli is an old friend, and I used it as my high-proof stabilizing component, to infuse the 16 botanicals I chose for what became Northeast No. 1.

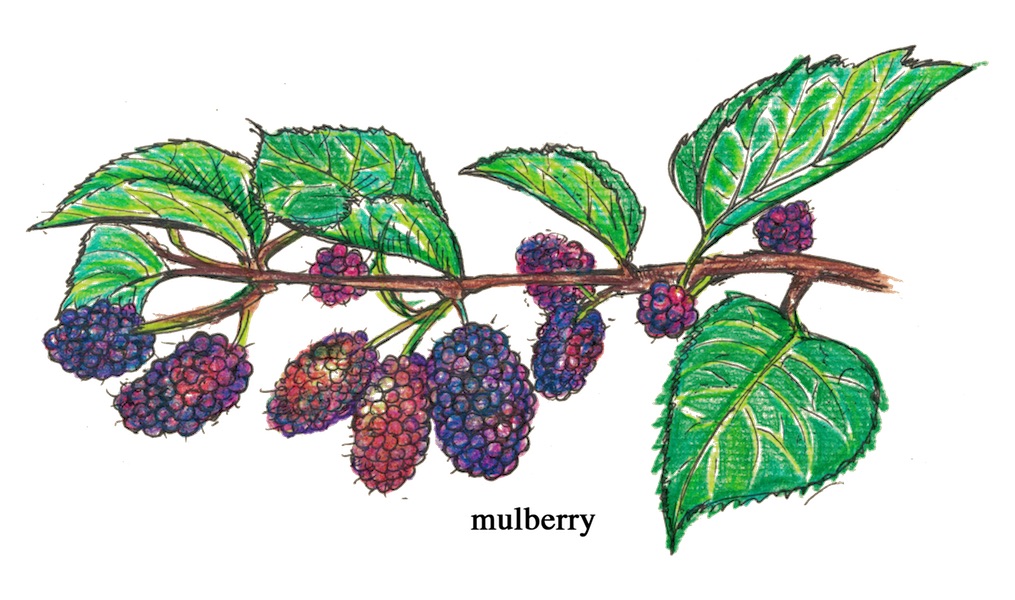

Foraged infusions included mugwort, mulberries, elderflower, indigenous bayberry, juniper, spicebush and sumac. I bought the customary black pepper, pink peppercorns, cardamom, clove, vanilla beans, lemons and raspberries, and added homegrown coriander and marjoram.

Each infusion was started at a different time (the longer herbs soak, the stronger the resulting bitters). On vermouth-making day, white wine was heated, sugar and fresh botanicals added, and then the high-wire act: deciding how much of each vodka-brew to contribute, without ruining the balance, and a considerable investment of time and resources. Northeast No. 1 was deep pink (the berries) and lightly floral; good enough to drink straight up, with ice and a lemon slice, and it mixes well with scented gins.

I moved on to Northeast No. 2, using the previous infusions, by now darker and more assertive. Traditional chamomile was introduced, as well as perfumed local pineapple weed. Northeast No. 2 was the color of tea, strongly herbal, more tannic. It blends superbly with brandy, bourbon and tequila, and holds its own with autumn syrups like rosehip and pomegranate. In the kitchen it handles deglazing well.

Increasingly, in terms of the edible and the potable, authenticity is synonymous with place. And the nearer, the better. My hope is that small-batch commercial producers narrow their focus to explore the exciting indigenous herbs and spices waiting under noses, developing a drink where the narrative is defined by local botanicals.

Employing the native American plants that grew here first, as well as the later invaders like mugwort and its cousins, will make American vermouth true.

Northeast Vermouth No. 1

Recipe by Marie Viljoen

For the vodka infusions:

Macerate the following botanicals in individual Mason jars. Use enough vodka to cover and give you the amount you need for blending—see below. You will have some left over; you can also increase quantities for a later batch of vermouth with a different character. And leftover vodka infusions make excellent bitters!

You will need about 1 liter of vodka.

10 days before you plan to blend the vermouth, macerate:

- 2 cups mixed raspberries and mulberries

- 1 cup raspberries (on their own)

5 days before blending, macerate:

- 20 bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) leaves

- 8 mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) sprigs; or 5 to 6 long sprigs

- 1 head of smooth or staghorn sumac (Rhus glabra or Rhus typhina—ripe in August), drupes removed from green stems; or substitute 3 tablespoons dried sumac in 6 tablespoons vodka

- ¼ cup spicebush (Lindera benzoin) berries

For the wine infusion:

The day before you plan to blend the vermouth, make the white wine infusion:

- 2 bottles unwooded white wine, not too acidic (chenin blanc works well)

- 10 juniper or Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) berries

- 1 tablespoon coriander seeds, toasted

- 1 teaspoon black peppercorns

- 1 teaspoon pink peppercorns

- ½ vanilla bean

- 3 pieces fresh lemon zest (2 inches each)

- 1 clove

- 1 stick cinnamon

- 1 cardamom pod

- 5 sprigs fresh marjoram

- 4 tablespoons sugar

Combine all the ingredients in a nonreactive saucepan over medium heat and heat till tiny bubbles rise at the sides of the pan. Do not boil. Allow to cool and infuse overnight. Strain through cheesecloth into a large bowl.

To blend vermouth:

- 4 fluid ounces (½ cup) raspberry-mulberry vodka

- 3 fluid ounces (6 tablespoons) bayberry vodka

- 3 fluid ounces (6 tablespoons) mugwort vodka

- 2 fluid ounces (4 tablespoons) spicebush vodka

- 2 fluid ounces (4 tablespoons) sumac vodka

- 2 fluid ounces (4 tablespoons) raspberry vodka

Measure the vodka infusions and pour them into the white wine infusion through a fine-mesh strainer. Then strain the combined mixture into a clean bowl through 2 layers of rinsed cheesecloth until the liquid is clear. Repeat if necessary, using clean cheesecloth. The vermouth is ready to be bottled. Pour it into sterilized, narrow-necked (less surface area for oxidization) glass jars or bottles with screw tops or spring enclosures.

Illustrations by Leslie Wang