The Team Behind The Four Horsemen Opens Its Second Restaurant, I Cavallini

Ten years ago, when Williamsburg was well on its gentrification journey but was still without an Apple Store, the Four Horsemen opened on Grand Street and changed what wine could be.

Originally a locus for the natural wines championed by their beverage director, Justin Chearno, as those vinos vini-ed and vici-ed their way to every list, liquor store, and fridge in the country, the eclectic, locally sourced menu under Chef Nick Curtola increasingly made the Four Horsemen a food destination.

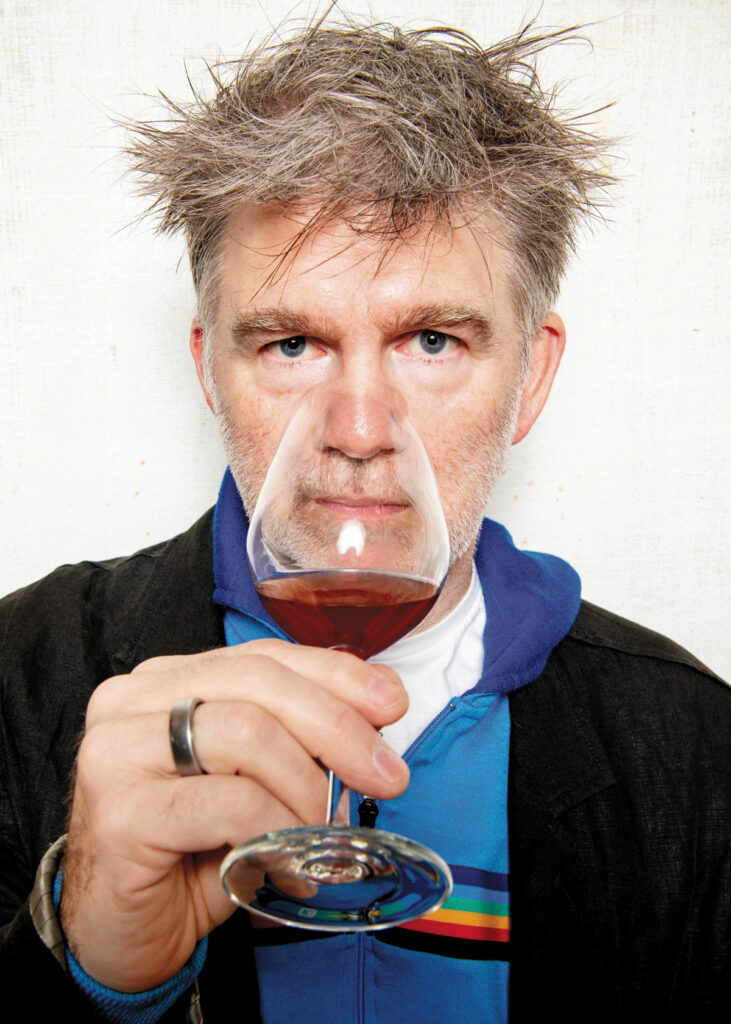

FEATURED IMAGE (TOP)

Foals Rush In. From left: Christina Topsoe, Amanda McMillan, Nick Curtola, and James Murphy, part of the team behind I Cavallini, a new Italian restaurant from the Four Horsemen team, where natural wine, this time from Italy, will still play a big role.

It remained quintessentially New York (unfussy, but rarefied, confident, and cool) but as Curtola’s menu evolved, so did the service, under General Manager Amanda McMillan, and something else began to take shape, something more formidable. Awards from James Beard and Michelin arrived and, like the neighborhood—as the hipsters thinned and tourists flocked, bathing in the robust culture reared by places like the Four Horsemen—it became undeniable.

Last spring, the team behind Four Horsemen (and Nightmoves, the audio-first, tight-doored dance club next door) took steps to open their second restaurant, I Cavallini, across the street at 284 Grand St. The restaurant would focus on Italian food from the Piedmont region (bordering France and Switzerland, think milky heartiness at its most refined). A lease was signed. A designer was hired. The menu and wine list were conceived. And then the unthinkable happened: In the fall of 2024, Justin Chearno suddenly passed away.

A wall of tribute to Justin Chearno, a champion of natural wine and one of the original “four horsemen” behind the wine bar that would receive not only a James Beard Award for wine under his watch, but a Michelin star as Nick Curtola’s food met and exceeded those standards. “He was such a heartbeat of the whole thing,” says McMillan, who is now managing director of all of the “Four Horsemen” operations. “When you lose somebody that’s such a pillar to what you’re trying to do, there’s part of me that’s, like, ‘Why are we doing this?’ It’s like the building burned down.”

The original “four horsemen” and partners in that restaurant were Chearno, Christina Topsoe, Randy Moon, and James Murphy (the founder of DFA Records who has one more job—fronting the band LCD Soundsystem). For I Cavallini, which McMillan and Curtola espoused, they have come aboard as stakeholders.

It is hard to overstate Chearno’s influence on both the Four Horsemen and the natural wine movement. To point at awards seems facile, and it’s perhaps most informative to revisit the 2020 New York Times review, which named the restaurant a Critic’s Pick: “In retrospect, the arrival of the Four Horsemen looks like a turning point for natural wine,” wrote Pete Wells. “Justin wasn’t classically trained. He didn’t take a bunch of sommelier classes. He was a musician, and he approached it in the same way that he approached music,” says McMillan. She says he told her to think of wine producers like artists, and importers like labels, the wine shops and restaurants like record stores: If you find a band you like, ask the guy at the shop what else he has in the same vein. “And he ran with people that were also super funny, not super stiff and stodgy. It was a really joyful approach,” she says.

When Chearno passed, the partners and those who knew and loved him gathered at the Four Horsemen. “His son Felix was here,” says McMillan. “He goes, ‘Are you still gonna open the Italian restaurant’? And I said, ‘I don’t know. It doesn’t feel right to do it without your dad.’ And he more or less interrupted me and said, ‘You have to do it. He’d be so mad at you if you didn’t.’ And I was just, like, well, there you have it.” Stacy Fisher, Chearno’s wife, is the restaurant’s sixth partner.

McMillan and the team got to work. Chearno had left notes for the wines (he wanted the list to feature 250 ever-changing bottles focused on Italy and the Mediterranean: “things like aged Barolo, new young winemakers from Campania, unicorn wines from Sicily, certain wines from Sardinia,” according to a note McMillan found in the office they shared). And more importantly, he’d passed along his knowledge to the staff.

“After a while, I was just, like, ‘Dude, we’re not building a cement wall; we’re tending a garden,” McMillan says. “And I think that’s what makes a restaurant really great. Everything you do, if you’re doing it well, requires a lot of care and attention.” Part of that was asking staff who had worked for years with Four Horsemen to step up. “I’m confident because I have such a good team right now that I feel excited to give them the chance to really shine,” says Curtola who’s appointed Ben Zook, a longtime sous at Four Horsemen, as chef de cuisine at I Cavallini. “I’m going to guide the ship, but I’m really looking forward to letting this next generation of cooks and chefs see what they have.”

While on any given night the Four Horsemen’s ability to draw from wide-ranging influences for their menu drew acclaim, Curtola is relieved to be faced with the parameters of Italian cooking.

“There’s only a few boxes it has to check: Is this a dish you’d actually find as a regional dish in Italy? And does it taste really good?” says Curtola. “It’s going to be…I don’t want to say ‘easier,’ because we’re still going to make it hard on ourselves,” he says. “That’s kind of what we do.”

For the menu, he is envisioning plates that take advantage of the rich resources of the Piedmont region. “I worked there almost 20 years ago,” says Curtola. “I was blown away by the more dairyfocused food, and a little more of the older cuisine, too. Piedmont is very medieval. I mean, there’s castles all over the place. And it’s a cold region, so the food is leaning more on the comfort side of things.”

He’s envisioning “a couple pretty big pastas” made as much as possible in house along the lines of a “classically formatted Italian restaurant with antipasti, primi, secondi, contorni.” The key for Curtola will be “exploring untapped regional dishes,” while taking in classics like vitello tonnato, and “Tajarin, which is a handmade, high egg yolk pasta, very thinly cut,” and agnolotti del plin, which is stuffed with roasted meats, like veal, rabbit, and pork. His eyes can’t help but travel to goats and game, wild hare, and boar (what the Piedmontese call cinghiale), “with a lot of cheese and butter,” he says.

As a wine director, they’ve hired Flo Barth, who wants to do for natural winemakers in Italy what Four Horsemen did for French ones: “The idea is to focus on things that are made by young women winemakers, things that are a little bit off thebeaten path,” she says. She wants the price point to be approachable, too. “I love Nebbiolo, but we’re not going to have as much Barolo as we are going to have Alto Piemonte wines, things like that.”

The space—open, with tall ceilings—has an exposed brick wall and custom wooden cabinetry from the previous owner, which they’re keeping. It will be minimal and friendly, warm and welcoming, drawing some inspiration from Brawn, a London wine bar and restaurant all the partners love. There’s an outdoor area and patio (“It has grapevines—like, actual grapevines—overhead,” says McMillan), and a bar big enough for a cocktail program. Most importantly, the space is much larger than the Four Horsemen.

The fact is, dining is different than it was 10 years ago, or even five. Social media has changed the landscape; everything is expensive, and not just New York expensive—expensive expensive; walk-ins are a fantasy after 5:30, and the possibility of a reservation has subsumed New York’s unofficial motto: if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere. “Just the last year and a half, I feel like there’s been this huge influx of superhigh-end chefs that are opening up really cool spots,” says Curtola. “In general, diners are a lot more educated than they used to be. And I also think it’s gotten a lot more expensive. I mean, I know that it has” says McMillan. “We have to make all this effort to make it worth their while.”

“I wanted to emulate the Four Horsemen in regard to the level of service that we offer and the warmth,” says Curtola. “I think what makes it really special is our staff. I mean, the food, the wine, the service, everything is very genuine and authentic.” A good deal of that authenticity, that attitude, could be traced back to Chearno, and what he imparted. “It’s almost like I have, like, a little WWJD bracelet that’s, like, What Would Justin Do?” says McMillan.

And here the ambition for Cavallini crystalizes. “People come to Four Horsemen to really take advantage of our deep cellar to order big on the menu,” she says. “We miss the casual drop in, pull up a chair, kind of attitude that we were able to have when we were a younger restaurant,” she says. “We’re going to have double the seats across the street.”

“I hope it will be the neighborhood place that the Horsemen can no longer be,” says Murphy, standing just a few feet from a shelf of wine bottles and photos that serve to commemorate Chearno. “Because it’s too busy.”