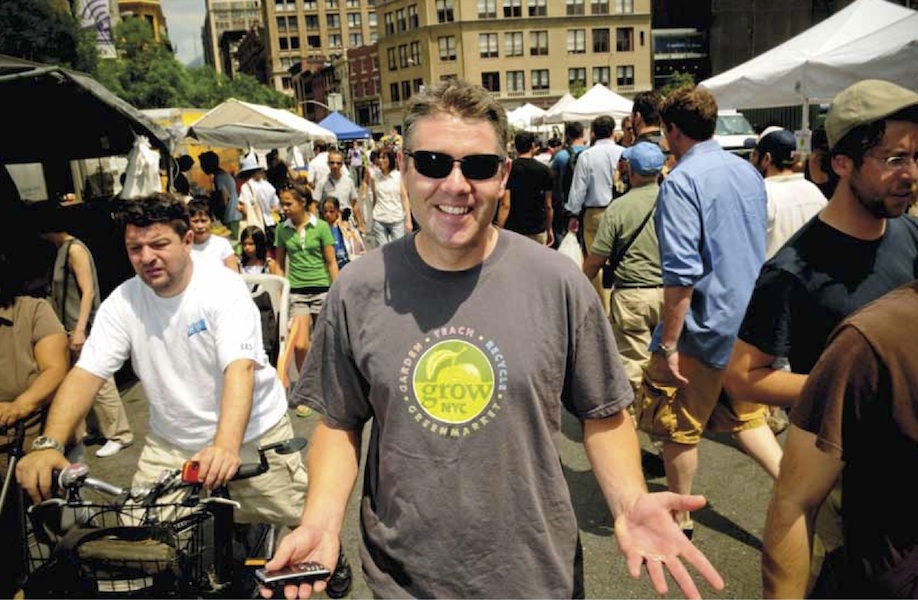

It’d be easy to imagine that Davy Hughes, the head manager of the Union Square Greenmarket, begins each workday over a breakfast of fried duck eggs and heritage bacon shared with the apple-cheeked growers who produced them, or at least a few fat plums and a wedge of farmstead cheese scarfed down on a city sidewalk in the morning sun.

But when Davy—who for nearly nine years has been the official on-site overseer of every square foot of that longtime locavore mecca run by GrowNYC, the nonprofit that launched the city’s Greenmarket program back in 1976—parks his beat-up van near the corner of 17th Street and Union Square West at five a.m., it is still dark. Even in September, it’s chilly enough for a sweatshirt, and, save a few drunken stragglers and a few slumbering farmers (most drive in around six a.m., but a couple arrive by three and nap till dawn), Davy is the only one in the park.

Every Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday of the year, the 39-year-old begins market day early. But during late summer and early fall, when area farmers hit peak harvest and the bumper crops are bumping into each other, Davy’s arrival time is what you’d call “the wee hours.” He downs an extra-large coffee and reaches for his most trusted early-morning tool: a roller-wheel attached to a piece of chalk. It’s just like the kind the traffic cops use to take down violators, and Davy, as it happens, knows plenty about parking.

Sure, he’s a serious home cook who can name gooseberry and garlic varieties faster than many of the city’s best chefs—most of whose direct dials are in his BlackBerry— but his daily duties have surprisingly little to do with pondering produce. It turns out that running the city’s biggest farmers market has more do with sidewalk chalk than Swiss chard, and Davy often spends more time with cops than cukes.

True, the program’s mission is to promote regional agriculture and ensure urban access to fresh local food, and Davy’s boss, Greenmarket director Michael Hurwitz, oversees that big picture from the GrowNYC office down on Chambers Street, where Davy meets with him each Thursday. But in pursuit of those macro objectives, Davy’s primary street-level task is to engineer the best way to choreograph the nearly 100 trucks driven into Manhattan by Greenmarket growers—who will likely breakfast at a bodega. (It’s fast and cheap, plus you can go in wearing muddy boots.) When it comes to masterminding a continuing supply of real ingredients for New Yorkers, Davy’s secret weapon is not a chef’s knife but measuring tape—though over the years, there have been plenty of occasions when a 12-inch Messermeister might have come in handy.

On fall Saturdays before the first frost, there can be more than 80 farmers, bakers, fishers and foragers at the market, some with multiple trucks. Most Davy directs inside the narrow asphalt ring around the northwestern side of Union Square, while a few unload and drive on to another market, in Tribeca, say, or on the Upper West Side. (At one stand, Sycamore Farms, a second truck arrives around noon with a delivery of that morning’s corn.) All reasons why Davy has to start his shift in the dark: “Phase one is chalking spaces and getting trucks into place,” he smiles: “No shit-shooting till sunrise.”

He marks the precise spot every last truck and tent will take, careful to leave a 20-foot customer aisle. That would be tricky enough even without the fact that fields and yields fluctuate with the seasons and weather, prompting last-minute calls as farmers whose grapes ripened early want to arrive a week before they were scheduled, or need an extra few feet to display an unexpectedly exuberant crop of melons. “On Friday, Migliorelli Farms might say ‘I need three spaces tomorrow instead of two,’” says Davy with a sigh, squinting in the scant light at the map he fine-tunes on his Mac all year long, tweaking feet here and there as crops ripen, “and we have to figure out where to put them.”

That they do. Once he and crew have marked it all out in chalk (“this looks tight,” says Davy, standing over the rectangle where the Van Glad brothers will soon sell maple syrup) they’ll have to lead those trucks laden with Jersey tomatoes and Pennsylvania peppers and upstate lamb—arriving, at least in theory, at carefully staggered intervals—right into their spots, waving them on like those guys at the airport do with planes. Inevitably a farmer destined for the center of the market arrives late, and occasionally there are worse mishaps: The pretzel van bumps the wine stand on one day, an aging farmer is narrowly missed on another, and then there was the time Mike Yezzi from Flying Pigs accidentally backed his load of pork chops and bacon into a phone booth.

But on most days, the scores of stands are safely in place by sunrise. And that’s when “Phase Two,” as Davy calls it, can begin. (Though only after a much-needed pee-break at Starbucks, since Whole Foods and Barnes & Noble, both of which house sweet upstairs bathrooms, won’t open till 10 a.m.) Think of Union Square on Saturday as a United Nations in session, with Davy as diplomat for the Country of GrowNYC, which runs not just the Union Square flagship but 50 more Greenmarkets citywide. At some point between a staff meeting at eight a.m.—Davy oversees a crew of three who handle operations, three who run marketing and public relations, and Eric, the security guard who patrols for shoplifters—and the time the City Harvest volunteers show up to bag leftovers at seven p.m., Davy’s got to go keep peace with all the other nations claiming a piece of the park. “We have all these tensions,” he explains, “farms, trees and park, the people, the artists, the musicians, film crews, food writers, ConEd…. You’re in the middle,” he says of himself and his staff, “getting sandwiched.”

There are the street people sleeping where a stand needs to set up and Betty the tamale lady, whom Davy used to have to evict since she didn’t grow her own corn. (Now Betty hangs out in a safer space near the subway entrance and the GrowNYC crew buys her gorditas.) There’s Barbara, the city park ranger who’s worried about corn silk and fresh fish water spilled on the sidewalk, or one of those 80 trucks bumping into a newly planted tree. There are the artists (and the con artists) who encroach the southern tip of the market with candles and canvases citing First Amendment rights to be there, the guest chefs who come in to host cooking demonstrations around 11 a.m., and the sunscreen-slathered volunteers working the information booth, smiling through endless harangues about food politics and purchasing: “Why isn’t this muffin labeled that it’s not gluten-free?” “Where are the grapefruit?” “Why don’t you sell more meat?” “Meat is murder!”

There’s his boss, Michael Hurwitz, the Greenmarket director, who passes through between meetings about increasing foodstamp redemption or a pilot to get more local produce into bodegas. There’s the NYPD , who wants to know which farmer tried to punch the other, or whether Davy can once again move the old Greenmarket van on West 16th Street out of the way for a movie crew. (There’s also now a spiffy new van, which serves as a mobile command unit, storage closet and ad for GrowNYC, complete with a paint job by New Yorker illustrator Marcellus Hall.) There’s the out-of-place Porta-Potty, like the one Davy tried to move, the egregious effluent spilling out and ruining his shoes. There’s the press-tagged photographers seeking the perfect tomatillo shot for the Times, the dozens of chefly regulars like Peter Hoffman on his bike, a big-wheeled cart from Momofuku, and vans from Blue Hill and Jean-Georges (most others hail cabs), and the random, rangy musicians who park themselves among the nutty, streaky-green patty pan squash and sweet, sweet Finger Lakes grapes called “Canadice.”

“That banjo guy,” says Davy, “is driving me crazy.”

And last but certainly not least, there’s the all-important nation of farmers, every member of which wants at least an hour of Davy’s time to grouse about too little rain, too much rain, shuttering slaughterhouses, MIA farmhands, corn borers, potato beetles, the imperfection of the federal organic standards and the endless injustices at the hands of other farmers, who have some nerve raising pigs this year when they know the guy across the aisle makes his whole entire living selling only pork; or who were spotted just that morning buying illicit Florida-grown tomatoes from Stew Leonard’s on the way to market.

“I’m glad you came to get my side of the story,” one guy angrily says to Davy, just as another calls to say he needs to drive his van through the market even while the multigenerational crowd is still so thick with buyers of habanero peppers, bi-color corn, purple kale and plum jam that it would make the most seasoned traffic cop shiver.

Maneuvering those carnival-like crowds, dashing between the crates of scallions at Mignorelli’s now extra-large stand, behind the tubs of geese and pheasant at Quattro’s Game Farm over on 17th Street, or the dripping white coolers filled with Long Island squid on Union Square West, Davy, who runs marathons on his downtime, literally covers miles before noon. Though it’s his ears that get the real workout. “Part of your job is just giving them time and listening to them, letting them know that you actually care about them,” says Davy, and it’s clear he does.

He somehow even finds a few seconds to shop. Even on Saturdays, between endless laps, between the madness of street buskers and the tens of thousands of buyers going bananas over the bacon and berries, Davy pauses long enough to nab the choicest products on offer. He coos over the duck breasts one farmer’s just brought to the market, dreamily wondering aloud how to best cook them; pauses over the tiny, sweetly nutty wild greens called “lamb’s quarter” Windfall Farms sells by the quarter-pound, and lingers over the fat, blushing, deep-purple President plums around for only a few days a year, and the multi-culti half-pints of heirloom chilies and tomatoes Tim Stark famously sets at his Eckerton Hill Farm. All require a quick dash to the cooler he keeps in the corner of his own van.

“It’s never stationary,” Davy says as makes a five p.m. sprint to the nearby Mud Truck. There he’s greeted warmly over his third coffee of the day, which will revive him for the six p.m. official close of market, when empty trucks trying to make their way out of the market—though some will stay to sell past dusk. “It’s ebb and flow.”

Those ebbs include early-morning ice deliveries (the Greenmarket receives it from an ice delivery company and provides it to farmers who need it to keep fish and fowl cold on hot days), collecting outstanding fees for spaces, and keeping detailed records about what each farmer brought in to sell.

That’s because in addition to keeping order on-site, Davy and his team work closely with their colleagues in the GrowNYC office downtown to ensure integrity to Greenmarket’s strict grow-your-own rules: Greenmarket’s no-nonsense Farm Inspector—often at market herself—checks Davy’s notes against what’s actually growing on each farm, and thus catches anything fishy. Like the guy who brings in 10 cases of cilantro in September, but whose field of the herb was harvested by August. The records also assist in maintaining product balance. Sure, Greenmarket could just rent spaces to anyone who applies, but instead Hurwitz and staff carefully consider the mix of stands: If a fruit farmer starts raising chickens for eggs, that might mean needed extra income for his family, but it could also hurt the family selling nothing but eggs up the aisle. Greenmarket wants both those farmers to thrive, and to feel the not-for-profit served them well.

But even when they don’t, Davy—whose pink cheeks, blue-green eyes and lilting musical voice reveal his Irish heritage—has a remarkable ability to stay unruffled, even cheerful in the face of chaos and the constant buzzing of his GrowNYC-issued BlackBerry. (For much of the day, the market is so thick with shoppers, the only way to find your coworkers is through the smartphone’s push-to-talk.)

But he’s both a social butterfly and a fierce believer in real food, a man so committed he even runs his own farmers market in Jersey on his Sundays off from 14-hour shifts at Union Square. Davy admits his job is exhausting, that he’s contemplated quitting for all the reasons you’d expect: It’s emotionally and physically draining, especially on 102-degree scorchers when greens wilt by nine a.m.—or the 12-degree January afternoons when turnips freeze to the table. Still, the highs outweigh the lows.

“It’s a community, it’s addictive, it’s a rush,” says Davy with a smile so wide you imagine he’ll still be here between the carrots and the kale at age 75.

City Harvest volunteer gleaners come to bag up the last of the unsold corn and radishes as the crowds are thinning out. Finally Davy’s pace can slow from lightspeed to languid, a moment made even more cinematic with the long rays of the setting sun. The farmers pack up their crates, count their cash, maybe hit Heartland Brewery for a pint—after relocating their now-empty trucks to a real parking space. Davy sweeps up the husks and pits as they go, surveys the vast emptying plaza as if it had all been some kind of dizzying dream, climbs into his van and drives west—nearly 15 hours after he left home, another market day done.

Photo credit: Max Flatow