Contemporary cruises are a curious form of travel—an entire vacation spent in transit, where the mantra is “all you can eat” and the main attractions are the midnight buffet and the chocolate fondue fountain. But modern cruises have their culinary roots in the old tradition of transatlantic crossings when on-board dining was more about glamour than gluttony.

Crossing the Atlantic by sail-powered ship took as long as two months, but in the mid-19th century, steam-powered ocean liners trimmed the voyage down to a more manageable trip of one to two weeks. Throughout the 19th and early-20th century, NYC was the primary point of departure for all ocean liners bound for Europe; during the heyday of ocean-going transportation, as many as a dozen passenger ships arrived and departed from the Hudson’s piers every day. The Times marveled at the amount of food needed to sustain 1,600 passengers during a typical transatlantic voyage: 14 steers, 10 calves, 29 sheep, 26 lambs, 9 hogs, 8½ tons of flour, 400 pounds of tongue and sweetbreads and 600 pounds of oatmeal and hominy.

In the 19th century, meals served on the high seas were a far cry from haute cuisine. Passengers had to make do with fixed-menu table d’hôte service. If stormy weather didn’t kill one’s appetite, the offerings—such as jellied eel—certainly could. But by the turn of the century, steamship lines began catering to their increasingly cosmopolitan clientele. When enterprising ocean liners introduced à la carte menus in 1907, they quickly gained a competitive edge.

One-way passage to Europe in a first-class cabin cost about $5,000 in today’s dollars and shipping lines used cuisine to vie for wealthy clients. Some recruited well-known chefs from the finest hotels in New York and Europe—the Hamburg America Line even signed an exclusive contract with the Ritz’s renowned restaurateurs. Other liners went to great lengths to serve fresh food at sea. The SS Kasierin Auguste Victoria featured an on-board garden, complete with a hothouse heated by steam from the ship’s boilers. The garden yielded fresh vegetables for the ship’s restaurant and even included peach and cherry trees where passengers could pass time gathering fruit. On a transatlantic trip, fish could be surprisingly hard to come by. To remedy this, one ocean liner installed a massive tank filled with bass and trout where passengers could supervise the catching of their dinner.

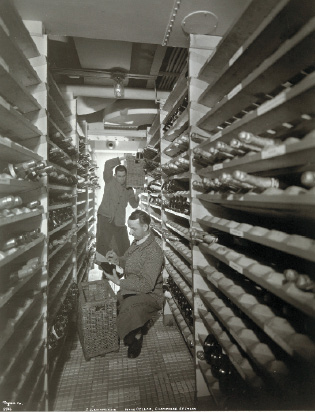

To wash it all down, wine parings were drawn from extensive on-board wine vaults, which contained thousands of bottles from around the world. By 1910, the Times noted that it was possible to set out to sea without forgoing any of city life’s luxuries.

Photo credit: Byron Collection, Museum of the City of New York