https://www.instagram.com/p/BERNf8UjAdD/

Who’s responsible for this world we now live in where chefs are revered and your friends who can barely boil water watch Chef’s Table? There’s an argument to be made for Jeremiah Tower, whom Anthony Bourdain has bluntly called “the first fuckable chef.” Tower helped shape Berkeley’s Chez Panisse into a revered institution before leaving in 1978, and went on to open San Francisco’s seminal restaurant Stars in 1984 (it closed in 1999); in 1996, he won the James Beard Award for Best American Chef. Isn’t it odd, then, that most people haven’t heard of him?

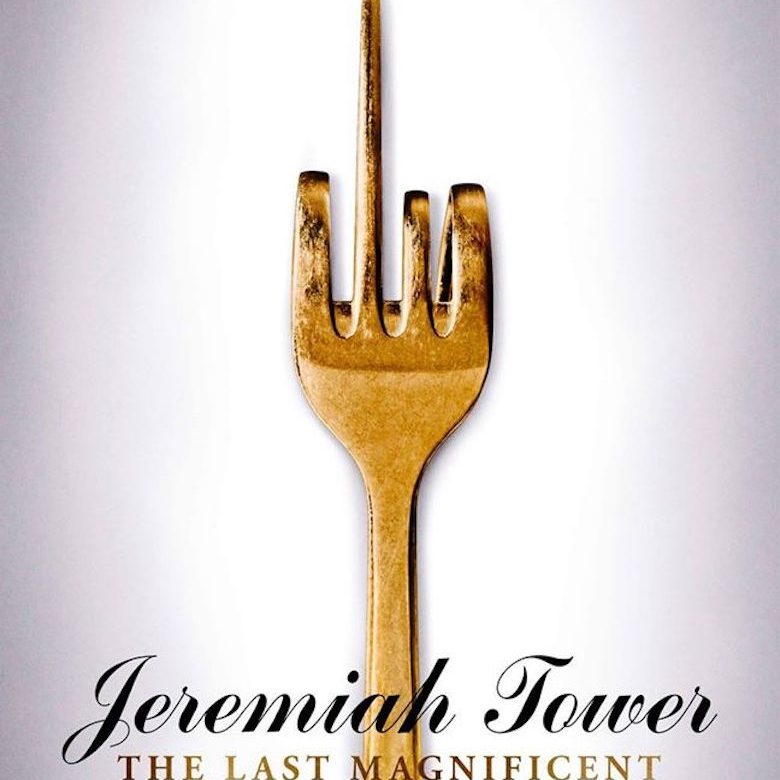

That’s what the documentary Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent, executive produced by Bourdain, seeks to fix. It paints Tower as ornery yet unfailingly polite, brilliant but ill-suited for business. How did a chef of his talent and regard end up disappearing to Mexico, then reemerging in 2015 to make a brief attempt at resurrecting Tavern on the Green? Go see the movie, opening on Friday at Sunshine Cinema, for a deep exploration of that question, featuring input from Mario Batali, Ruth Reichl, Martha Stewart and others who knew him personally or were influenced by his work. Here, we talk to Bourdain about why he wants to help Tower take his rightful place in the culinary canon.

Edible Manhattan: Why, personally, was this an important movie for you to make?

Anthony Bourdain: I was really affected by Jeremiah’s memoir [Start the Fire: How I Began a Food Revolution in America] when I read it a few years back, and it pressed my justice button. I felt that this was a story that needs to be told. This is a really, really important chef, a really important person in the history of a business that I was involved in for 35 years of my life, and I felt I had an opportunity to do it. I have creative partners who could make the film well and a likely customer in CNN who would put up the money, and I thought this would be a fun thing to do and good for the world.

EM: It’s a lot less sumptuous and food porn-y than a lot of food series we’re getting accustomed to. Who do you think the audience for this is—restaurant nerds, or is there now a wider audience for this sort of documentary?

AB: It’s a character study. When you have a good, powerful character, I don’t have to know anything about or be particularly interested in the subject matter. We didn’t make this film for foodies. I think it’s a good story with a fascinating character.

I just saw a play on Rosalind Franklin, the researcher on DNA—one of the people essentially responsible for discovering the secret of life—the last thing in the world I’m interested in is two scientists sitting in a laboratory talking about DNA strands, but it was a riveting two hours because the characters were so great. Jeremiah Tower is a great character. I think people who have no interest in food whatsoever will find something to love in it.

EM: How did you select the array of talking heads in the documentary?

AB: People who knew Jeremiah back then were obviously a priority, people who were there in those days who could speak to actual events—who were there for them—I think were the people we went after first. Then people who were very much influenced by what Jeremiah did: Mario Batali, Ken Friedman. Or writers who kept the flame alive, like Regina Schrambling, who for years had been almost alone in talking about Jeremiah’s importance when much of the rest of the food writing community were lazily complicit in his creation myth. There was life in the food world pre-Jeremiah, and there was life in the food world post-Jeremiah.

EM: Do you think that Jeremiah’s problems in being in restaurants were a problem of his or of other people not understanding him?

AB: Both. Look, Jeremiah is a strong personality—an artist, a creative person who had a very different approach. The things that were interesting to Jeremiah and the things that were important to him were not necessarily the most important things to maintaining a long-term, successful business empire. I think that’s clear. He didn’t do a lot of things that chef friends of mine have to do, who are more fully aware of the environment of the business operates in—who work hard to maintain the care and feeding of people who will be helpful to them. I don’t think Jeremiah was particularly good at that. The people that Jeremiah wanted to love him—I don’t think they were necessarily the same people who needed to be massaged, stroked, maintained, cared for and fed. Jeremiah wanted something else. He was a romantic and the world that he looked to for inspiration and felt connected to was very far from the vulgar realities of business in contemporary America to some extent. A lot of Jeremiah’s heart and soul is in Paris in the 20s and 30s.