Edible Institute chewed on everything from why cooking is a revolutionary act (Bittman) to why we should be eating more filter feeders (Greenberg) and veal (Barber) to how campaign finance reform is the path to public health (okay that was a passing comment, but I enthusiastically tweeted it because it’s true). Marion Nestle even role-played calling Senator Gillibrand (played by Anna Lappé) to support regulation of marketing junk food to children.

In other words, if you missed it, you missed out.

I was riveted to my seat in the audience but, for an hour, had to un-rivet myself to join a panel on independent media, moderated by Sam Fromartz from the Food and Environment Reporting Network, alongside environmental journalist icons whose ink cartridges I’m not fit to refill, from stalwart institutions like Mother Jones and Harper’s. We discussed independent food media’s assignment to, as I’ll put it, galvanize the public to bring about food-system change. Riffing on Upton Sinclair, we need to hit readers in the heart, not the stomach. There was mention of editors’ inscrutability and the vexing practice of slapping screaming headlines atop subtle writing. (More on this in a moment.)

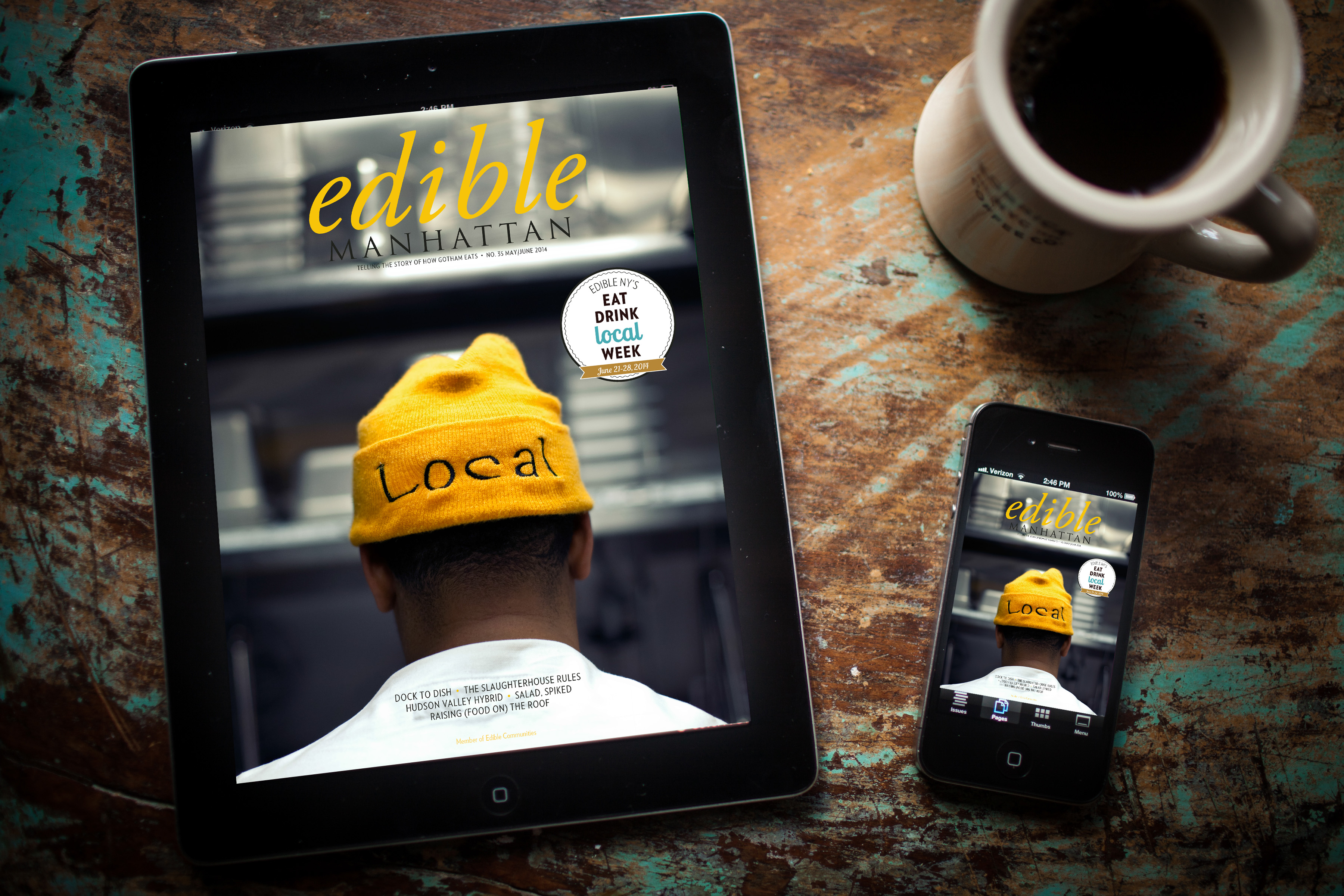

I talked about how the barriers-to-entry for content creators have crumbled to dust in the digital age. You no longer need exposure through the Today Show or Time magazine to share your message. Anyone with Internet access can share ideas through Twitter and the blogosphere — which, as both a media producer and consumer, I regard as enormously exciting, but not without cons. There’s been an explosion (or as On the Media put it, a supernova) of available content. But consuming it can be like sipping from a firehose. And competition for eyeballs is unprecedented. The (New York) Times, they are a-changin–because people like me only read it on our phones anymore.

The next morning I woke up thinking of something I wish I’d said. Here goes:

I see a parallel between the changes in the food environment and the changes in the media environment. Fifty years ago, Americans did not swim daily in a sea of junk food. Sure, you could get your hands on a lollipop, but for the most part, food was nutritious. We all know how that’s changed. Cue B-roll of every retailer in the country, from Wal-Mart to Staples, luring us with brightly colored supersize packages of sugar, salt and fat.

There’s something similar afoot in the media world. A generation ago you could subscribe to MAD magazine and catch Tom and Jerry, but for the most part, what I’ll call nutritious information did not compete with endless other temptations like Sochi bathroom slideshows (which I sure clicked through) and on-demand seasons of Girls (I’ve been known to eat the whole bag). The good news is that today you can get more varieties of organic arugula — and its media equivalents, from Heritage Radio and EarthEats to CivilEats and Modern Farmer, to hey, the website you’re now reading — than young Alice Waters could have dreamed of. But we producers face enormous competition for the attention of the American eater, and reader.

I have a vision, and it’s not entirely pretty. I picture publications like Mother Jones and the Atlantic as trays at a buffet holding delicious, healthful offerings, cooked by professionals and subtly seasoned. A generation ago, there wasn’t much else to choose from. Today, the buffet has grown from a few tables to 100 blocks of skyscrapers, with every room on every floor of every building crammed with ceiling-high piles of chocolate-covered bacon and sriracha-drenched tacos, aka streaming videos and click-bait listicles. Yes, there’s more media-broccoli than ever, if that’s what you want (I reach for my phone before dawn each day to click posts about new projects in Alabama or policies in Brazil; sometimes I even read past the second paragraph). But the 1950s broccoli-to-lollipop ratio, in both food and media, is flipped. We are bombarded with omnipresent invitations to snack on empty calories of the mouth and mind. In this buzzy, Buzzfeed environment, will serious journalism be able to serve its meritorious messages to many people for much longer?

I think the answer is: only with aggressive, inventive adaptation. Which doesn’t mean this. Instead, it does means almighty writers like Tom Philpott must not only help the public connect the dots between our diet and our planet, those writers must also take up the serious assignment of how to attract readers to their table at the buffet. I’ve seen the future, and it’s not printed on paper.

Am I calling for 200-word posts, slide shows instead of 5,000-word features? Am I siding with editors who favor those screaming headlines? I don’t know. But I do know the world needs to ingest what people like Philpott are saying. It’s essential to our species’ survival. Which means those serious stories must be served on screens in ways that are delicious enough to keep people reading to the end, and coming back for seconds and thirds, for years to come.