Last October, a wine bar called V-Note opened on the Upper East Side. It was trumpeted as a “vegan wine bar,” and offers biodynamic, organic and sustainable wines to pair with its animal-free food.

No New Yorker blinked.

Why would they? Gotham is awash in wine bars of every stripe, and has been for some years. They have become so idiosyncratic and specialized that it’s possible to find one precisely catered to your taste no matter how specific your oenophilic tendencies. Like South African wines with your South African cuisine? Head to Xai Xai in Midtown for your dose of pinotage. Think the wines of southern Italy are undersung and underdrunk? Point your feet toward In Vino in Alphabet City, where Basilicata and Calabria are never forgotten. Worship riesling? Terroir Tribeca, where Germany’s noble grape is on tap even, is your fatherland.

In short, Manhattan’s bibulous are spoiled. But it wasn’t always so. This embarrassment of wine bar riches is a relatively new phenomenon, born of the current infant century. There had been a spurt in the early ’80s, the result of the 1970s wine boom. The hot spots typically focused on old-school French wine and mainly clustered around SoHo, which was on the verge of its heyday as the center of the art world. But it was short-lived, and by the decade’s end, in New York a wine lover’s mouth could easily dry out between glassfuls.

Then a few glimmers of light appeared. There was Etats-Unis (now closed); and Le Bateau Ivre, which opened in January 1999 and is still going strong on East 51st Street, billing itself, rather long-windedly, as “New York City’s first true French wine bar.” And there was Morrell Wine Bar & Cafe.

In New York’s relatively young wine-bar world, Morrell rates as a founding father. The very name has become a sort of synonym for “wine bar,” shorthand in its mercantile realm in the way institutions like FAO Schwartz and Brooks Brothers are in theirs. It is perhaps the one wine bar in the city that even nondrinkers know by name.

Morrell’s position is partly owed to the fact that it’s held firm to its ritzy, high-profile inner berth of Rockefeller Center Plaza, opposite the skating rink, and that it continues to pack in tourists and locals alike, most every night.

But one also must take into consideration that the business’s city roots go deep. This is not just a 12-year-old wine bar, but a 12-year-old wine bar run by a 63-year-old wine store. The Morrell story began in 1947, when the parents of wine bar cofounders Peter and Roberta Morrell swung open the doors of a liquor store on 49th Street near the Waldorf-Astoria. By 1998, the business—run by Peter, Roberta and Roberta’s husband, Nikos Antonakeas—was facing a dwindling lease, when Rockefeller Center came calling. Tishman Speyer Properties had just bought the landmark complex of office towers from Mitsubishi and was determined to bring actual New Yorkers back to the ur-New York address.

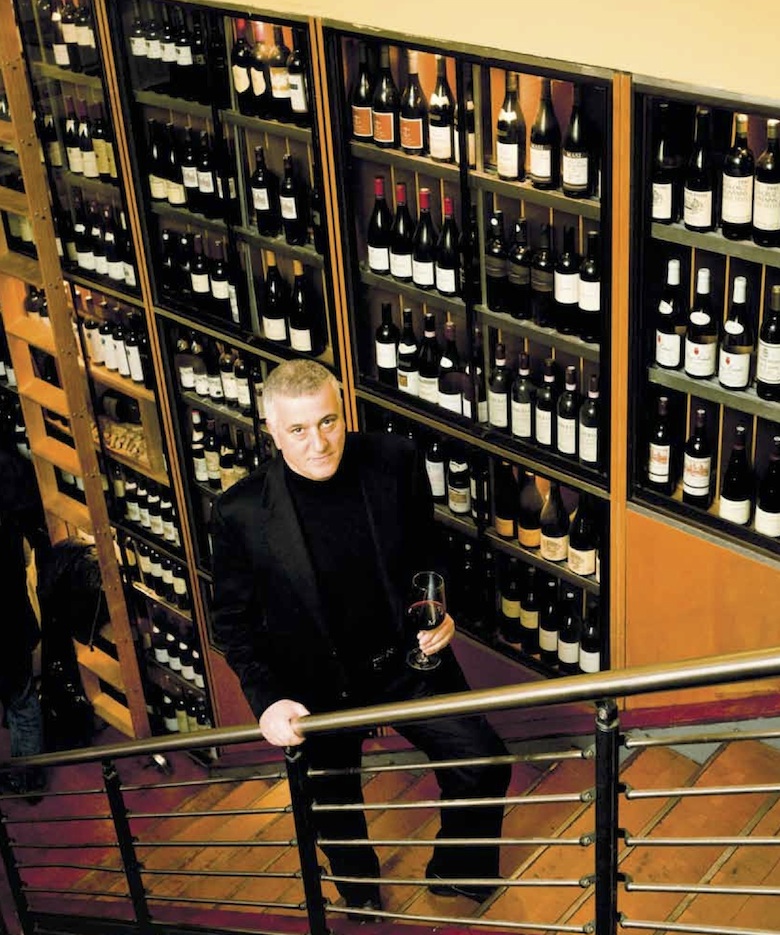

“We were called,” recalls Antonakeas, a distinguished-looking Athens native with a European’s love of food and wine and a New Yorker’s penchant for wearing black. “We were not looking to move to Rockefeller Center. We thought they would be out of our reach. They said, ‘No, we’re looking for an established name to bring New York back to Rockefeller Center, because it has been nothing but airline ticket stores and banks.’”

Antonakeas and the Morrells agreed to take a look around. But the Tishman rep was only opening doors on 49th and 50th streets, nothing along the inner plaza. “She said, ‘Management really wants to save those spaces for restaurants, food and wine,’” recalls Antonakeas. “And I said, ‘We can do that.’”

Antonakeas had wanted to do a wine bar on Madison Avenue, but the landlord was skittish about the idea. So at Rockefeller Center, Morrell became a side-by-side two-store operation: wine store on the left, wine bar and café on the right. True to Tishman’s plan, the wine bar took over a space formerly occupied by an American Airlines ticket counter. In fact, under the current wooden floor is buried a huge brass eagle, the emblem of the airline. “It would have cost more to remove it than to actually leave it there for posterity,” chuckles Antonakeas. “It’s for people to find in years to come.”

Roberta Morrell, who married Antonakeas 27 years ago, executed the design of the snug cantina. “I wanted two things,” she says. “I wanted it to look like a fun place, to be very convivial. And I never wanted it to look empty—even when it was empty.”

Toward that end, she created an undulating front bar that pushed hard against the front window. “I realized you can talk to everyone on a curved bar. On a straight bar, you can only talk to the person next to you. And wine people talk to each other.”

Antonakeas knew from the start that he wanted to serve food, not just bar nibbles. “What bar food will do is make it a bar,” he says. “You can cut the wine out—it will be a bar. If you want to make a wine bar that is doing justice to the theme of wine, wine is a complement of food. I almost never drink wine by itself. In fact, if I am at a bar and I don’t intend to eat, I might as well have a Scotch.”

Morrell Wine Bar & Cafe made an impression right away, offering 100 wines by the glass—an amount not unheard of today but especially remarkable at the time. Critics cottoned to it, but it took a while for the public to catch up. “The first year was what I call the fishbowl effect,” says Antonakeas. “They were looking through the glass. They were not sure if this was a restaurant, a tapas place, a wine place. ‘Can I have a beer?’” After about a year, it caught on with people who work in the neighborhood. “Rockefeller Center is a microcosm by itself. Tens of thousands of employees work in the buildings of Rockefeller Center, above and beyond the tens of thousands of visitors, which are mostly tourists.” Soon, NBC employees and editors from Simon & Schuster and Macmillan were coming for lunch two or three times a week.

Morrell benefited from a sea change in the country’s attitude toward wine. “Americans were getting interested in wine,” says Antonakeas. “They were really saying to themselves, ‘that’s an extension of food.’ Until that happens, wine is not part of the culture. If you treat it only for special occasions, and it’s not an extension of your meal, it doesn’t become part of your life.”

New York Times writer and food historian William Grimes remembered the bar’s arrival. “The wines on hand were good, of course, and the food was, too. It was nothing spectacular, but the whole wine-bar ethos was pretty much bistro-level. You were looking for an imaginative wine list—a chance to try choice wines without reaching deep in your wallet for the price of a full bottle. I imagine some people used them as testing grounds, sampling wines and then buying a bottle or case.”

A year after Morrell’s launch, the business found itself in good company, and the New York Times observed a sudden crop of wine bars. “In the past few years,” wrote Frank Prial of the trend, “about 20 places calling themselves wine bars have opened in New York, some to considerable acclaim, and none could be more different from (the) dinosaurs (of the past)…. Wine is still important, but the pomposity is nowhere to be found.”

“Within a year, actually, all of a sudden it became fashionable, the thing to do,” says Antonakeas.

Nikos’s wife says she wasn’t surprised at all by the boom in wine awareness. “What I didn’t think was that most of the bars would be Italian,” Roberta Morrell comments. “We are the exact opposite. And to this day I don’t think there’s anyone who’s replicated what we did. We started with wines by the glass, from everywhere. South African, New Zealand, French, Italian, and at all price ranges. And when we opened, we had a first growth by the glass.” The luscious and prized dessert wine Château d’Yquem by the glass was another early attraction that has since become somewhat commonplace (Le Bernadin and the late Cru, for instance, have offered it), as was Dom Pérignon on pour. By 2003, Time Out New York intoned, “as wine bars proliferate faster than Duane Reades, you’ve found comfort in a classic: stately Morrell Wine Bar.”

A stately classic—after only four years.

Stately, it does seem, even today. And not just because of its imposing address (1 Rockefeller Plaza!), glass-and-gold facade and narrow-but-soaring two-tiered architecture. The clientele is very obviously well-heeled. There’s no need for a dress code here. Crisp dark suits, ties and fine jewelry accessorize the twisting bar. And patrons don’t shy from ordering glasses of Italian Super Tuscan Tignanello and the big-boy Napa Cab Insignia. Roman Roth, the respected East End vintner, calls it “a great meeting point, especially for guests from overseas.”

Who you won’t necessarily find perched in Morrell’s window seat are the hirsute, wool-hatted members of the younger oenophile set, for whom Morrell now feels a bit middle-of-theroad, a place for the Wine Spectator–reading establishment. And critics have, to a large extent, moved on to newer drinking dens like Ten Bells on the Lower East Side, known for pouring the natural offerings of small producers, and Bar Henry in Greenwich Village, where patrons can order half pours of many bottles, the remainder of the wine then being offered to the room by the glass.

They are no longer sent aflutter by Morrell’s celebrity patrons, like legendary theater director Hal Prince, who works nearby, or the Chilean-wine-loving Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino, who drops by every time he’s taping a sports program in New York.

“It’s pretty conventional,” says Tyler Colman, the author of the wine blog Dr. Vino, proffering faint praise. “Could you or I find a wine that would keep us happy during a lunch with a publisher? Yeah. But it seems like it’s for a crowd that knows what it wants already. If you’re looking to be challenged, you’re not going to be necessarily pushed into buying something that you’re not familiar with. It is serviceable for people who find comfort in labels.”

Fair enough, perhaps. It’s true you probably won’t find people at the Morrell bar chatting about biodynamic methods or the oxidized orange wines of Friuli. The Morrell list is more traditional, less esoteric. But, of course, wine elitism goes both ways, and there’s another side to that argument. Roberta Morrell, who regularly checks out rival wine bars, remembers one visit vividly.

“We were in a little tiny wine bar that had six or seven seats at the bar and maybe 20 in the place. Nikos ordered a wine from Sicily and I ordered one from Sardinia, and when they came, they were so hot that I looked at him and him at me and I said, ‘Ice cube?’ He said, ‘Why not?’ That’s one of the things people have said to me, that we serve wine at the right temperature. The whites aren’t too cold and the reds aren’t too hot. So we asked the guy behind the bar to put an ice cube in each glass. We’re talking about $6 glasses, now. He did, and then turned around and said to the other guy behind the bar, ‘Some people don’t know anything about wine.’”

“That’s us,” she says in the tone of an adult who long ago learned to tolerate the impudence of youth, “the people who don’t know anything about wine.”

Idea on the rise: Nikos Antonakeas wanted to serve food, not just bar nibbles. “I almost never drink wine by itself. If i am at a bar and I don’t intend to eat, I might as well have a Scotch.” Photo credit: Michael Gross