As I walked through the Hudson Valley forest, my steps padded by a blanket of damp leaves, I had the sensation that I was walking backward in time.

That’s because I was with Andy Brennan and Polly Giragosian, the husband and wife behind Aaron Burr Cidery, an operation that’s digging through the annals of history to put forth a cider made using 19th-century practices—complete with apples picked from 200-year-old trees. I was along on one of their late-fall forays through long-abandoned homesteads, in search of the fruit of forgotten trees that had seen neither pesticides nor modern tools, apples whose juice Andy would allow to ferment naturally, thanks only to the magic of wild yeasts.

Andy likes to let nature take its course. In fall, he spends entire afternoons climbing through vines and blackberry brambles to bring home only a few bushels of apples. It is painstaking work, but to Andy it’s well worth it. For these apples—and the alcohol they’ll yield—contain flavors that cannot be replicated in a modern orchard or conjured up through the artificial flavoring found in today’s mass-market ciders.

Which is why, in only two short years of business, Aaron Burr Cider now appears on menus of top restaurants and bars like Gramercy Tavern, Eleven Madison Park, Eataly, Bierkraft and Hearth (where I work). Andy has quickly risen to the top of America’s burgeoning cider renaissance, not just for the quality of his ciders but also because of his nonconformist and sometimes controversial approach. For in a world where technology typically trumps tradition, Andy is an artist caught in time, a homesteader who offers us a taste of another life, one glass at a time.

With an appearance straight out of Central Casting—the first time I met him, he was unshaven, wearing wool pants, suspenders and a rubber band to hold back his hair—he is reminiscent of Edward Norton gone mountain man. Polly, a painter who also draws and works with fiber and textiles, wears an ever-present smile. They moved up from Brooklyn and here, in Wurtsboro (population 1,246), have carved out a life that steps off the grid and into the past—the golden age of hard cider.

Cider was America’s daily drink for 250 years, when every American with land grew apples not for eating—those varieties were far too tart—but for fermenting into hard cider. Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and John Adams were accomplished orchardists and cider makers, as was just about everyone else in America from the 1630s to the 1880s. But the temperance movement vilified cider as sinful, and legions of axe-wielding teetotalers stormed the fields.

In the early 20th century, the apple industry nimbly repositioned its fruit as something to snack on—an act of rebranding that would make Apple’s marketing department blush—and soon America was widely replanted with the far sweeter “eating apple” varieties you grew up on. It is only now, nearly a century after Prohibition’s repeal, that hard cider is roaring back into fashion.

America’s 10 best-selling cider brands (led by Boston Beer Co.’s Angry Orchard and Vermont Cider Co.’s Woodchuck Hard Cider) grew 62 percent in 2012, and although it’s still a niche market, suddenly everyone wants a piece of the apple alcohol pie. The large beer companies including MillerCoors, which recently bought out popular craft cider house Crispin, and AB InBev that produces Michelob Ultra Light Cider and Stella Artois Cidre have moved in with gusto and are snarfing up market share by creating products that taste like apple soft drinks, primarily using imported apple concentrate.

Traditional cider apples are quite different than anything you’ll pick from the piles at D’Agostino. So punishingly acidic and tart, they’d turn your face inside out if you tried to bite into them like a Golden Delicious—but press them and ferment the juice, and you’ve got liquid gold.

Apples are grown worldwide, but as with any agricultural crop, do better in certain climates. The Northeastern U.S. is in one of these Rolls-Royce regions and, as Andy puts it, “the Hudson Valley is dead-center of the Western Hemisphere’s apple belt. We live in the premier apple region, second or third worldwide only to the Tien Shan Mountains and Caucasus Mountains of Asia,” where the earliest form of the apple appeared perhaps 10 million years ago.

But Andy, 43, didn’t end up in Wurtsboro with a plan to make cider. First and foremost a painter, and by trade an architectural draftsman, he took a much more spiritual path—in pursuit of an orchard he once loved, and lost.

“I’ve been haunted by a ghost orchard,” he explains. In his 20s and 30s, he escaped Brooklyn summers for a ramshackle fishing shack on the Chesapeake Bay surrounded by an old, abandoned orchard. “It was magical,” he says, “endlessly inspiring.” He painted there, finding peace in its majesty—until a developer bought the property, cut the entire orchard to the ground and burned it in a massive pyre. Andy was gutted. His sanctuary was gone and he couldn’t shake the loss.

Back in Brooklyn, he and Polly decided to look for a place in the Hudson Valley where, as Andy puts it, “we could replant that orchard from Maryland.” In 2006 they purchased 100 acres from a family that had inhabited the land for 150 years. On it stood 10 old apple trees.

As fate would have it, the 2007 season produced a bumper crop of apples in the Hudson Valley—on tended orchards but also the untamed branches of long-forgotten trees Andy found on his walks through the woods. He took a truckload to be pressed and, already familiar with beer making, experimented with fermenting the juice. The result was unlike anything he had tasted.

Intrigued, he sought out and sampled serious ciders by Farnum Hill and West County and, as he recalls, “It all clicked.” Andy felt a calling, a cider vocation.

So the following year he got an antique press and, in the cellar below their new home—no doubt swirling with the spirits of previous inhabitants—began pressing apples he’d picked in the woods nearby.

“Down there in the damp, dark dungeon and experiencing the cold,” he recalls, “slowly tuning into the increasing soil temperature and longer days—I realized, this is the life I’m drawn to.”

He enrolled in ag extension classes on farming, forestry and fermentation, but quickly became skeptical of modern methods after being told that apple trees would not grow in the soil on his farm.

They already did, and produced beautiful fruit.

“Every bit of what they argue has been disproved by history,” Andy says of the mainstream tenets taught in the extension classes he took. “Was wine made before chemical inoculation and cultivated yeast? Of course. Do apples grow without human intervention? Of course. I‘ve been told so many things about growing apples, making cider or running a business that just aren’t true.” Like a lover of lard piecrust told to use Crisco instead, he turned away from industrial advice and let nature and history be his guides.

At the core of his operation is the use of apples from very old trees—especially those he found on abandoned cider orchards (mostly along the Shawangunk Ridge near his property) that had been absorbed by the forest—many of them planted by homesteaders in the early 1800s. These trees couldn’t be more different than the sun-bathed, neatly aligned trees in orchards today. Nearly 30 feet tall, they hadn’t seen pruning shears for a century.

But the essential difference is in the fruit itself. Great cider needs a “trinity” of sugars, acids and tannins. Riddled with blemishes and looking more like something that came out of the ground than grew on a branch, the apples of long-forsaken varieties are often higher in sugar but also higher in acids and tannins. They’re spittably bitter—but perfect fermentation fodder.

He pressed his haul and let the juice ferment naturally—choosing not to inoculate with commercial yeast as his former teachers had instructed, instead trusting that spontaneous yeasts from the apple skins and the air would begin the magic process of fermentation on their own. It was risky and time-consuming but yielded a vibrant cider with a purity of fruit that left him intrigued by the possibilities.

He licensed the operation in 2011, naming it Aaron Burr Cidery—the well-known dueling Revolutionary figure had signed off on a transfer of their land a couple hundred years prior—and bottled the nation’s “first licensed cider made from wild, foraged, noncommercial apples.”

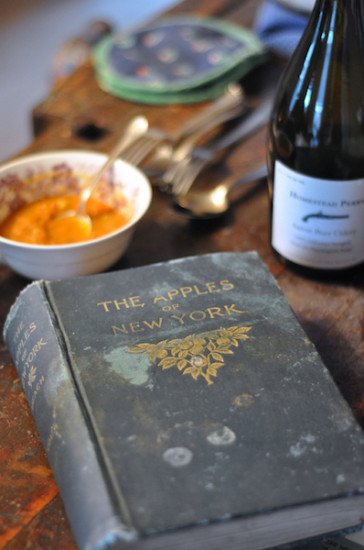

Not that he won’t touch an apple that grew in a farm field. The following fall he foraged, pressed and fermented. By Christmas, the juice was in barrels, last April he began blending the various lots, and come June, the cider was ready for market. Of the six ciders he released last year—Homestead Apple, Ginger Apple, Elderberry, Traminette (blended with Finger Lakes grape must), Golden Russet and Homestead Perry (made from wild-foraged pears)—three were made from forest-foraged fruit and three from apples on neighboring farms. Production is tiny: only 30 cases of Homestead Apple, for example. The interest was immediate, as city drink kingmakers fell for the fruits of his labors—and the story behind them.

Ben Sandler, owner of the Queens Kickshaw, a beer and cider bar in Astoria, was an early supporter. “His ciders are intensely flavorful and bracing in their originality,” he raves. “They are a true expression of passion.”

Juliette Pope, wine director at Gramercy Tavern, bought bottles and instantly recognized the uniqueness of his quixotic quest. “Andy’s dedication is clear. He’s on a single-minded pursuit of something esoteric, historical, variable and chancy, all at once.”

And Cory Bonfiglio, bar manager at Proletariat in the East Village, says the Homestead line “may be the truest expression of local terroir available to us in New York City.”

But while the Slow Food crowd is impressed with tales of his technique, the taste speaks for itself. Andy’s Homestead Apple cider, for example, pale yellow with delicate tiny bubbles, pulses with energy and pureness of fruit as it dances across the palate, finishing dry with notes of cinnamon and a hint of earth.

Predictably, Andy passes all the credit to the fruit, and seems interested in objectives that have little to do with the bottom line. “The reason I’ve been seeing a lot of attention,” he says, “is because of the apples I use. They’re simply more alive than their zooed-in relatives. And I will sacrifice profit for authenticity. This is one of the most intimate connections we have on Earth, and it is far more important than business.”

The more hours he’s spent with trees that turned “wild” as the woods enveloped them, the more he feels that forest ecology is actually better for growing apples. He and Polly have planted over 400 trees on their property—but don’t picture straight rows all in a line, with only mowed grass between them. They’ve grafted traditional cider apple tree cuttings (both cultivated and wild) onto rootstocks, and instead of clearing the land, are letting the environment do what it will. Assuming the deer don’t munch the trees to nubs, their orchard (which spreads nearly five acres and is mostly in forested sections) will bear fruit in three to five years.

In Wurtsboro, I was surprised by how rugged their life is. Any romantic notions of running off to embrace my tree-hugging nature went out the drafty window—this is not a living, it is a way of life. Polly teaches studio art at Orange County Community College, and Andy continues his day job as a draftsman. They just eke by financially.

But that may change. Andy needs support from the cider community to make his dream of cider’s full return a reality—and he’s getting it from some very established people. His products are literally fought over by the Manhattan beverage community (I threw some elbows myself just to get a couple of cases) and, more to his point, he’s inspiring people to rethink our connection to the earth through the apple. What he envisions is nothing short of cider’s second coming.

“We have to get the local population to bond with the soil once again,” he muses. “Eventually, a culture will reestablish itself and then high cider will return.”

Savor more of our cider content with these six stories from our archives.