Why We’re Loving Mid-Century Middle American Food

The conversation at the next table turns from tales of dorm woe to the food that just landed on the table; it happens to include a dish of duck Salisbury steak. We are at Patti Ann’s Family Restaurant, Chef Greg Baxtrom’s ode to Midwestern cuisine in Prospect Heights, and I am shamelessly eavesdropping. The speaker, currently in college, opines that she “just loves this kind of food.” I spin my head. Unless this circa-20-year old has a time machine, she’s probably too young to have had it.

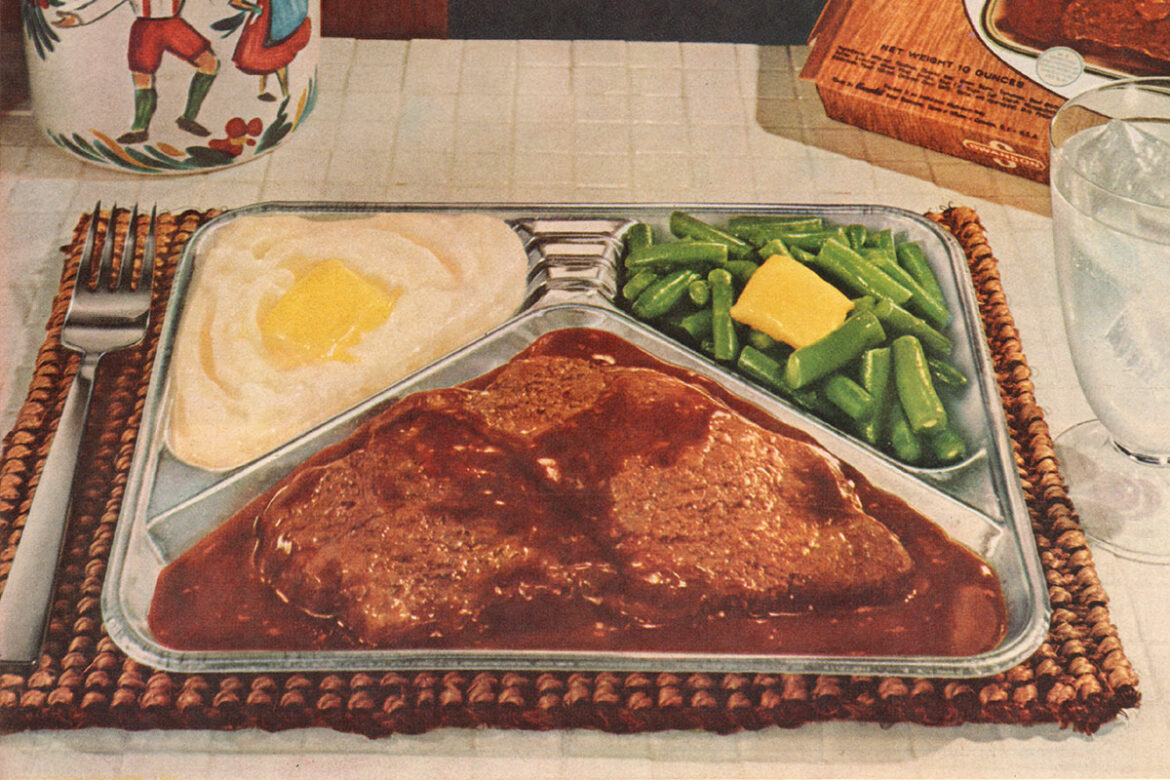

I am well out of college, and I have never spotted a Salisbury steak in the wild. I’ve only seen the dish in relation to Swanson TV dinners, which were literally branded “Swanson TV Dinners” at their birth in 1953. Turns out, the dish—which, to my knowledge, exists solely in the triangle-shaped compartments of foil trays—is the ultimate Midwestern food. It was invented in Missouri by a Dr. James H. Salisbury, who, having been a physician in the Civil War, came up with the completely batshit, Road to Wellville theory that dysentery could be avoided if soldiers stuck to a diet of coffee and beefsteak. Vegetables, obviously, were to be avoided because they caused tumors and tuberculosis. Obviously. Salisbury, like Michigander Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (he of the cereals and 15-quart enemas), was a classic American character: a fad diet promoter.

Of course, at Patti Ann’s, I order the duck Salisbury steak, and, but for the choice of protein, it is just how I imagine a Swanson Salisbury steak should be: fork-tender, salty, and robed in a shiny, almost sticky, deeply brown sauce. It tastes … faithful to something, even though I’ve never eaten Salisbury steak, foil or no foil, before. It also tastes brave. As in, Baxtrom’s take on this cuisine doesn’t fit into the bougiefied comfort food craze of the ’90s (that launched a thousand truffled and lobster mac & cheeses). Instead, this dish is flat-out evocative of, if not reverent toward, TV dinners.

Baxtrom grew up in a small rural town in the Illinois corn country south of Chicago; his father was a carpenter and his mother was an elementary school teacher—at Patti Ann’s (named after Baxtrom’s mother), the menu riffs on her profession in cocktails called the Parent Teacher Conference and Field Trip. Growing up, sometimes Baxtrom ate TV dinners, an experience that he reflects on with neither blame nor shame. “My parents had three kids that were all in high school at the same time. We were all in sports, you know, so it was, like, first one home, throw the thing in the oven.” In re-creating the dish for Patti Ann’s, Baxtrom avoids the temptation to, as he says, “make it fancy by incorporating Wagyu or something obnoxious, you know. We use duck and let that be what’s different. Then we try to make it taste as much like the TV dinner as we can.”

While it is brave to embrace a cuisine so many have mocked—most hilariously by James Lileks in his Gallery of Regrettable Food—it’s still braver of Baxtrom to refrain from calling attention to his craft on the menu. At Patti Ann’s, its most famous dish is simply listed on the menu as Pig in a Blanket, with no explanation offered at all. This menu does not whisper that the pig in question is a lush brick of Nueske’s bacon (straight outta Wisconsin), wrapped in a tweaked, rollable version of Patti Ann’s potato roll dough. This is pointedly not Frenchified puff pastry. Instead, Patti Ann’s potato bread ingeniously mimics the soft, mild, canned crescent roll dough of Pillsbury’s mid-century back-of-box recipe for “Piglets in the Blanket.”

A lot of thought went into Patti Ann’s Pig in a Blanket, and, without sharing the process, those efforts will be missed by some diners, who won’t get Baxtrom’s winking use of curly parsley garnishes, either. But Baxtrom doesn’t want his cheffy process to become an ego-feeding hurdle between diners and their dinners. “This way, the person who doesn’t give a fuck about how creative I am still loves the food.”

As if TV dinner inspo isn’t enough, Baxtrom dips into reverence for chain restaurants and their trademarked dishes. At Patti Ann’s, the chef at the helm of Michelin-rated, sophisticated (and nearly saintly) Olmstead serves a Blooming Onion. It’s a riff on Outback Steakhouse’s Bloomin’ Onion®, and like its inspiration, it’s as big as your head. Or a cabbage. Or a bright red gym ball. Its sheer size—and most of the serving sizes at Patti Ann’s are outlandish by NYC standards—redeems every European sneer about American food portions. Worse, this massive, deep-fried root vegetable is paired with ranch dressing, which one wit once called “sorority sauce” for its biggest, blandest, and most basic fans. (Just so you know, the condiment was invented around 1950 by a Nebraskan.) In Baxtrom’s hands, both it and the onion are unspeakably delicious.

It’s a smart dish, funny, epically Instagrammable, and it works for large groups and kids—because, after all, Patti Ann’s is a “Family Restaurant.” That said, it comes from an experience that Baxtrom actually had: “I went home when I was in culinary school in Chicago, and my parents took me out to dinner. I had a Bloomin’ Onion. That’s the only time I’ve had it, so I must have liked it—or maybe I just needed that meal with my folks.” Even such lowly, trademarked, chain restaurant Frialator fodder evokes familial love.

New York City’s diners are a sophisticated tribe who—at the highest end—appreciate the nuanced differences between Chinese regional cuisines and, often, are conversant with even the most esoteric of vegetables. Yet, like that college kid at the neighboring table, New York has been receptive to the open-faced and friendly—practically Dockers-wearing—Middle American cuisine at Patti Ann’s. Baxtrom attributes this to the exhausting excesses of ego-driven menus, and, in part, to COVID. “People are fragile,” he says. “Now more than ever, people are in need of familiarity and a comforting meal that isn’t secretly pretentious.”

Baxtrom is not alone. New York City seems to have landed on the final frontier of food trends: American Provincial. It’s happening at Clinton Hill’s Brooklyn Hots, where Chef Brian Heiss is slinging Garbage Plates, a Rochester regionalism (though he calls his version “Trash Plate” because the originator of the dish—you guessed it—trademarked the name). It’s also at Pig Beach, where Chef Matthew Abdoo offers “Chicken Riggies,” a Utica-specific baked pasta not unlike the Midwestern mostaccioli at Patti Ann’s. There have been precedents; it’s hard to remember now that it has outposts in Malaysia, but Danny Meyer’s Shake Shack was inspired by the Steak’n Shake restaurants of his St. Louis youth. Meanwhile Baxtrom is in Brooklyn serving up pot roast and meatloaf sans irony, almost as a Zen rejection of ego, or an exercise in self-acceptance.

Despite his Midwestern youth, Baxtrom went on to cook at Per Se, Blue Hill at Stone Barns, and Alinea. When Olmstead opened in 2016, its vegetable canonizing menu earned Baxtrom accolades from The New York Times, New York Magazine, Esquire, Eater, and the James Beard Foundation. Yet there was a disconnect between the food that Baxtrom cooked in his career and the food culture that he lived. “I mean, it’s definitely something that chefs have—or at least I have—a hard time balancing. Like, OK, Olmstead is the culmination of my entire career, but none of that food is—on any level—food that I would ever put out in my house. So, what is that? What that’s saying is that I’m embarrassed by what I eat.”

Kitchen culture generally does not reward self-reflection, but at Patti Ann’s, Baxtrom is laying it all out there—his Midwesternism, back-of-the-box food culture, TV dinners—even the cream cheesy, paper-plated cheeseballs served at his family’s celebrations. “You know, these are the memories I have,” he says. “And, of course, I’m flexible— but if I can’t stick to those core memories, then what the hell’s the point?”

Patti Ann’s Family Restaurant

570 Vanderbilt Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11238

@pattianns_brooklyn

“Salisbury Steak” with 100% Ground Beef

Adapted from The Cookbook of the United States Navy (1945), this recipe for Salisbury Steak was originally scaled for 31 pounds of boneless beef. The recipe specs no cut (say, chuck or sirloin); it just reads “beef,” that tumor-fighting superfood recommended by health-visionary Dr. J.H. Salisbury. If you’re actually going here, we suggest dolling up the beef with ground mustard, Worcestershire sauce, ketchup—or pretty much ANYTHING—to taste.

Ingredients

- 1 pound ground beef

- ½ cup fresh breadcrumbs

- ½ onion, grated

- 2 tablespoons beef fat

- 2 tablespoons flour

- 2 cups beef stock (or just water, according to the frugal U.S. Navy)

- ½ cup milk (it’s not historically accurate, but cream would be better)

- Salt and pepper

Instructions

In a bowl, combine the ground beef, breadcrumbs, and grated onion. To be patriotic, season to taste with only salt and pepper (or be a traitor and add ground mustard, Worcestershire sauce, and a glug of ketchup). Form the mixture into four oblong, vaguely steak-shaped patties about ¾ inch thick.

In a nonstick pan over medium heat, sear the patties until they’re uniformly grey and unappealing. Set aside, reserving the fat in the pan. If necessary, add additional fat to pan to make 2 tablespoons.

With pan over medium heat, sprinkle the flour over the fat and stir the mixture until no lumps remain. Cook, stirring, until the mixture is lightly browned, a bit puffy, and no longer smells raw, about 1 or 2 minutes.

Slowly add the beef stock or water (!), stirring constantly; switch to a whisk if you’re worried about lumps. Simmer, stirring, until the mixture starts to thicken, then add the milk. Continue to cook, stirring, until the sauce achieves a sturdy, Navy-approved viscosity. Serve with something mushy and bland.

Featured image: “1967 Swanson TV Dinner Advertisement Life December 22 1967” by SenseiAlan is licensed under CC BY 2.0