New York Harbor is not just a choppy hurdle between Wall Street and the Red Hook IKEA. It’s not just a scenic backdrop for the Statue of Liberty. Instead, it’s part of a massive estuary centered on the mighty Hudson River, with associated wetlands, islands and inlets that reach all the way from coastal New Jersey to Connecticut. Think about New York Harbor as a part of New York State’s version of Chesapeake Bay. Now realize that, for millennia, these nutrient-rich waters were lined with oyster reefs.

The Billion Oyster Project is working to restore those reefs with the help of the city’s restaurant community. Its operating thesis is that one adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day. They estimate that one billion oysters will be able to filter the entire harbor in three days, siphoning off pollutants and the nitrogen that depletes oxygen in the water to create dead zones. In this program, which emerged from aquaculture studies at the Urban Assembly New York Harbor School on Governors Island, restaurants are contributing their spent oyster, clam and scallop shells, which make the ideal substrate on which new oyster colonies can grow. Once collected by the Project, these shells will eventually be seeded with oyster larvae and then sunk into the water in frames that will decompose, leaving behind man-made oyster reefs. The program aims for a virtuous cycle in which New Yorkers, having killed their oyster reefs with human and industrial waste, are now pulling shells from the restaurant industry’s waste stream to restore New York City’s oyster populations, which will, in turn, restore the health of our waterways.

It’s not surprising that the oyster, of all creatures, could be the one to save our waters—after all, New York and oysters have always been linked. The oldest evidence that locals loved oysters is a shell midden—a human-made discard heap—discovered along the Hudson River, in Dobbs Ferry, where the river’s water is tidal and brackish. According to Mark Kurlansky in his exhaustive history of New York and oysters, The Big Oyster, that midden was dated to 6950 BCE and is the earliest evidence of humans in the Hudson Valley, but Native American oyster middens were found all over New York City. Pearl Street is named for one (a misnomer—New York oysters don’t produce pearls).

RELATED: The New York City Oyster: Crassostrea Virginica

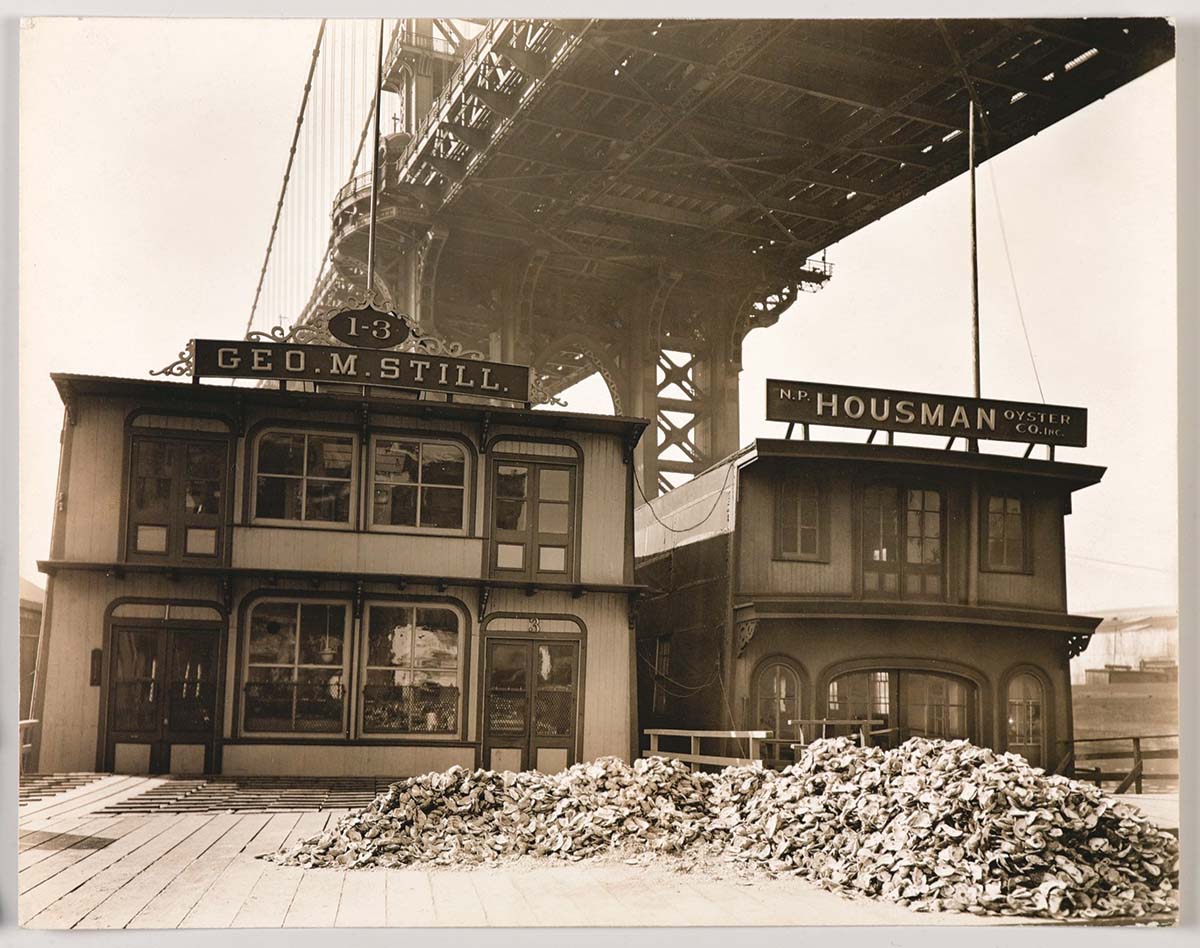

Dutch colonists, great letter writers, often wrote about the plenteous, massive and delectable oysters they foraged from the city’s shores, with particularly large specimens coming from the Gowanus Canal. By the 1830s and 1840s, New York City’s oyster-eating culture had become so established that oyster cellars advertised to illiterate and non-English-speaking diners with glowing red and white muslin lanterns. New York City oysters were exported as delicacies to tables in London and Paris, and there was a 19th-century version of AYCE, the “Canal Street Plan”: all the oysters you could slurp for 6 cents. Oyster carts abounded, slinging bivalves to dress curbside with pepper, mustard, lemon or oil and vinegar. As Kenneth T. Jackson notes in his Encyclopedia of New York City, by the 1850s, about $6 million worth of oysters were consumed annually by New Yorkers. By 1880, the oyster beds of New York were producing 700 million oysters per year. New York was Oyster City, USA.

The only thing New Yorkers ignore more than nature is history.”

– Mark Kurlansky, ‘The Big Oyster’

The last oystering operation in New York City closed in 1927; that was in Raritan Bay, in Lower New York Bay, adjacent to the Atlantic. Operations in Jamaica Bay, which once sent 80 million oysters to market annually, were already closed by 1915. The Upper Bay (aka NY Harbor) operations had closed earlier when the toxicity of its more inland water could no longer be ignored—this was after oyster dredges had already scraped up some of the valuable, ancient reefs. The killing blows came when periodic cases of oyster-born cholera and typhoid, spread by the fecal contamination of drinking water and food, had been linked to the city’s laissez-faire handling of raw sewage. Meanwhile, industries on the estuary had been sluicing out so much pollution that fishermen noted declining species even as the city’s oystering operations were achieving all-time highs. New York City’s oysters had started to taste like the petroleum being refined at Newtown Creek, which is now a Superfund site.

Today, on Governors Island there are two long, massive piles of shells, modern middens generated by New York City diners. They’re composed of the remnants of miscellaneous species of oysters, clams and scallops that have been collected from restaurants that include Per Se, Maison Premiere, and M. Wells. If you look closely, you can spot the occasional oyster fork or mignonette stain. Here the shells will remain for one year, until the risk of introducing foreign organisms to our water system is gone. Then they will be seeded and sunk in New York waters.

Since 2014, the Billion Oyster Project has restored 75 million oysters to New York City’s waterways. They’ve even brought substrate shells to the Hudson River, in Tarrytown, near where New York’s oldest oyster midden was found. So far, 7 million native oysters have voluntarily anchored upon these shells to thrive. In New York Harbor, restored oysters are growing in complex aggregates of tiny and large individuals, steadily enveloping the shells on which they were seeded, and then the frames that hold them, submerged in the waters off Lower Manhattan. Sadly, it could be as long as a century before these oysters are safe to eat. Nevertheless, each one grows and siphons continuously, doing its part to repair the damage of the last 150 years.

To learn more, volunteer or donate, visit billionoysterproject.org.

Feature photo by Lori Pedrick.